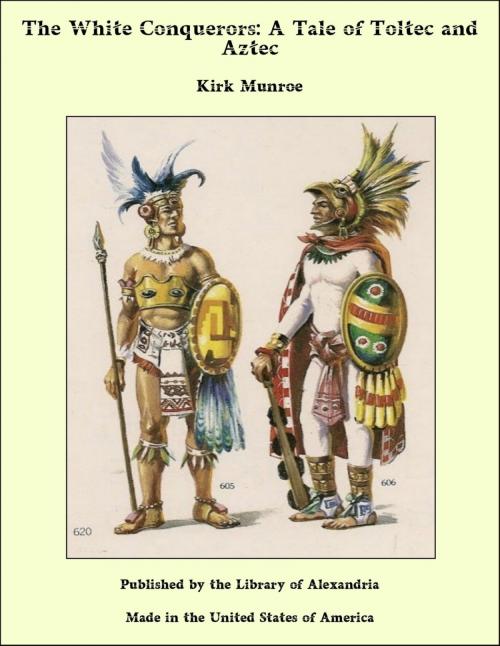

The White Conquerors: A Tale of Toltec and Aztec

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | Kirk Munroe | ISBN: | 9781465624543 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Kirk Munroe |

| ISBN: | 9781465624543 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

Night had fallen on the island-city of Tenochtitlan, the capital of Anahuac, and the splendid metropolis of the Western world. The evening air was heavy with the scent of myriads of flowers which the Aztec people loved so well, and which their religion bade them cultivate in lavish profusion. From every quarter came the sounds of feasting, of laughter, and of music. The numerous canals of salt-water from the broad lake that washed the foundations of the city on all sides, were alive with darting canoes filled with gay parties of light-hearted revellers. In each canoe burned a torch of sweet-scented wood, that danced and flickered with the motions of the frail craft, its reflection broken by the ripples from hundreds of dipping paddles. Even far out on the placid bosom of the lake, amid the fairy-like chinampas, or tiny floating islands, the twinkling canoe-lights flitted like gorgeous fire-flies, paling the silver reflection of the stars with their more ruddy glow. In the streets of the city the dancing feet of flower-wreathed youths and maidens tripped noiselessly over the smooth cemented pavements; while their elders watched them, with approving smiles, from their curtained doorways, or the flat flower-gardened roofs, of their houses. Above all these scenes of peaceful merriment rose the gloomy pyramids of many temples, ever-present reminders of the cruel and bloody religion with which the whole fair land was cursed. Before the hideous idols, to which each of these was consecrated, lay offerings of human hearts, torn from the living bodies of that day's victims, and from the summit of each streamed the lurid flames of never-dying altar fires. By night and day they burned, supplied with fuel by an army of slaves who brought it on their backs over the long causeways that connected the island-city with the mainland and its distant forests. These pillars of smoke by day, and ill-omened banners of flame by night, were regarded with fear and hatred by many a dweller in the mountains surrounding the Mexican valley. They were the symbols of a power against which these had struggled in vain, of a tyranny so oppressive that it not only devoted them to lives of toil, hopeless of reward, but to deaths of ignominy and torture whenever fresh victims were demanded for its reeking altars. But while hatred thus burned, fierce and deep-seated, none dared openly to express it, for the power of the all-conquering Aztec was supreme. Far across the lofty mountains, to the great Mexican Gulf on the east, and westward to the broad Pacific; from the parched deserts of the cliff-dwelling tribes on the north, to the impenetrable Mayan forests on the south, the Aztec sway extended, and none might withstand the Aztec arms. If the imperial city demanded tribute it must be promptly given, though nakedness and hunger should result. If its priests demanded victims for their blood-stained altars, these must be yielded without a murmur, that the lives of whole tribes might not be sacrificed. Only one little mountain republic still held out, and defied the armies of the Aztec king, but of it we shall learn more hereafter. So the mighty city of the lake drew to itself the best of all things from all quarters of the Western world, and was filled to overflowing with the wealth of conquered peoples. Hither came all the gold and silver and precious stones, the richest fabrics, and the first-fruits of the soil. To its markets were driven long caravans of slaves, captured from distant provinces, and condemned to perform such menial tasks as the haughty Aztec disdained to undertake. During the brilliant reign of the last Montezuma, the royal city attained the summit of its greatness, and defied the world. Blinded by the glitter of its conquests, and secure in the protection of its invincible gods, it feared naught in the future, for what enemy could harm it?

Night had fallen on the island-city of Tenochtitlan, the capital of Anahuac, and the splendid metropolis of the Western world. The evening air was heavy with the scent of myriads of flowers which the Aztec people loved so well, and which their religion bade them cultivate in lavish profusion. From every quarter came the sounds of feasting, of laughter, and of music. The numerous canals of salt-water from the broad lake that washed the foundations of the city on all sides, were alive with darting canoes filled with gay parties of light-hearted revellers. In each canoe burned a torch of sweet-scented wood, that danced and flickered with the motions of the frail craft, its reflection broken by the ripples from hundreds of dipping paddles. Even far out on the placid bosom of the lake, amid the fairy-like chinampas, or tiny floating islands, the twinkling canoe-lights flitted like gorgeous fire-flies, paling the silver reflection of the stars with their more ruddy glow. In the streets of the city the dancing feet of flower-wreathed youths and maidens tripped noiselessly over the smooth cemented pavements; while their elders watched them, with approving smiles, from their curtained doorways, or the flat flower-gardened roofs, of their houses. Above all these scenes of peaceful merriment rose the gloomy pyramids of many temples, ever-present reminders of the cruel and bloody religion with which the whole fair land was cursed. Before the hideous idols, to which each of these was consecrated, lay offerings of human hearts, torn from the living bodies of that day's victims, and from the summit of each streamed the lurid flames of never-dying altar fires. By night and day they burned, supplied with fuel by an army of slaves who brought it on their backs over the long causeways that connected the island-city with the mainland and its distant forests. These pillars of smoke by day, and ill-omened banners of flame by night, were regarded with fear and hatred by many a dweller in the mountains surrounding the Mexican valley. They were the symbols of a power against which these had struggled in vain, of a tyranny so oppressive that it not only devoted them to lives of toil, hopeless of reward, but to deaths of ignominy and torture whenever fresh victims were demanded for its reeking altars. But while hatred thus burned, fierce and deep-seated, none dared openly to express it, for the power of the all-conquering Aztec was supreme. Far across the lofty mountains, to the great Mexican Gulf on the east, and westward to the broad Pacific; from the parched deserts of the cliff-dwelling tribes on the north, to the impenetrable Mayan forests on the south, the Aztec sway extended, and none might withstand the Aztec arms. If the imperial city demanded tribute it must be promptly given, though nakedness and hunger should result. If its priests demanded victims for their blood-stained altars, these must be yielded without a murmur, that the lives of whole tribes might not be sacrificed. Only one little mountain republic still held out, and defied the armies of the Aztec king, but of it we shall learn more hereafter. So the mighty city of the lake drew to itself the best of all things from all quarters of the Western world, and was filled to overflowing with the wealth of conquered peoples. Hither came all the gold and silver and precious stones, the richest fabrics, and the first-fruits of the soil. To its markets were driven long caravans of slaves, captured from distant provinces, and condemned to perform such menial tasks as the haughty Aztec disdained to undertake. During the brilliant reign of the last Montezuma, the royal city attained the summit of its greatness, and defied the world. Blinded by the glitter of its conquests, and secure in the protection of its invincible gods, it feared naught in the future, for what enemy could harm it?