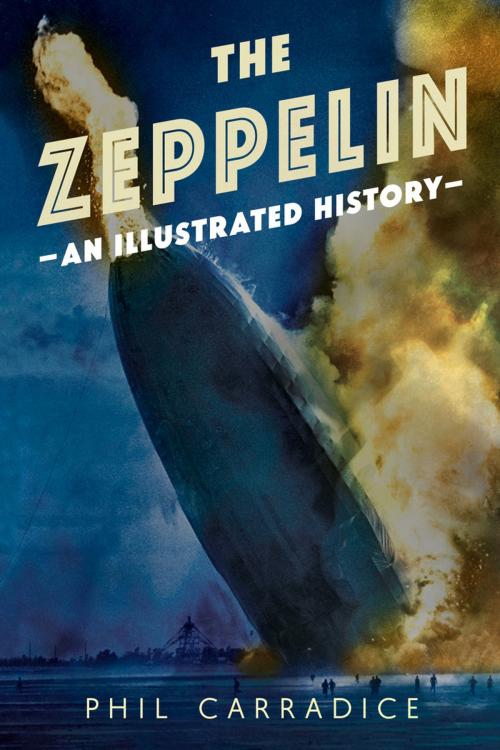

The Zeppelin

An Illustrated History

Nonfiction, Reference & Language, Transportation, Aviation, Commercial, History| Author: | Phil Carradice | ISBN: | 1230001908534 |

| Publisher: | Fonthill Media | Publication: | September 19, 2017 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Phil Carradice |

| ISBN: | 1230001908534 |

| Publisher: | Fonthill Media |

| Publication: | September 19, 2017 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

For a brief period in the early Twentieth Century, it seemed as if the future of air travel lay with the giant airships of Count von Zeppelin. The First World War ended that dream, fixed-wing aircraft superseding the slow moving and unwieldy airships. As weapons of war, the Zeppelins were never truly successful although they did manage to terrify huge numbers of unknowing and naïve civilians – perhaps more by imagination than by any practical manifestation of their power.

The Zeppelin crews of the First World War spent hours in the air, cold and hungry – and with the prospect of a horrendous death, either by fire or by falling thousands of feet to the ground, ever present. As vehicles of mass destruction, the Zeppelins were remarkably ineffective. Their real value, however, lay in their ability to make silent reconnaissance missions over enemy territory and sea lanes. In the post-war days, the public began to realise that airships offered a form of air travel that was comfortable, mostly stable and, sometimes, even luxurious.

The Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg were the height of elegance. Unfortunately, they had two major defects: they were vulnerable to the elements and, due to the hydrogen that kept them aloft, they were also highly flammable. The Hindenburg disaster of 1937 effectively spelled the end of the giant airship as a commercial enterprise but for almost half a century, these wonderful machines had cruised elegantly through the clouds.

For a brief period in the early Twentieth Century, it seemed as if the future of air travel lay with the giant airships of Count von Zeppelin. The First World War ended that dream, fixed-wing aircraft superseding the slow moving and unwieldy airships. As weapons of war, the Zeppelins were never truly successful although they did manage to terrify huge numbers of unknowing and naïve civilians – perhaps more by imagination than by any practical manifestation of their power.

The Zeppelin crews of the First World War spent hours in the air, cold and hungry – and with the prospect of a horrendous death, either by fire or by falling thousands of feet to the ground, ever present. As vehicles of mass destruction, the Zeppelins were remarkably ineffective. Their real value, however, lay in their ability to make silent reconnaissance missions over enemy territory and sea lanes. In the post-war days, the public began to realise that airships offered a form of air travel that was comfortable, mostly stable and, sometimes, even luxurious.

The Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg were the height of elegance. Unfortunately, they had two major defects: they were vulnerable to the elements and, due to the hydrogen that kept them aloft, they were also highly flammable. The Hindenburg disaster of 1937 effectively spelled the end of the giant airship as a commercial enterprise but for almost half a century, these wonderful machines had cruised elegantly through the clouds.