| Author: | Francis Marion Crawford | ISBN: | 9781465534651 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Francis Marion Crawford |

| ISBN: | 9781465534651 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

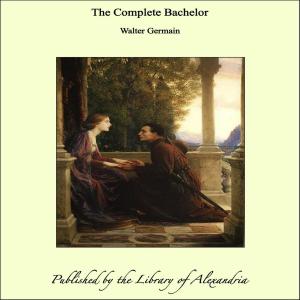

The Senator Michele Pignaver, being a childless widower of several years' standing and a personage of wealth and worth in Venice, made up his mind one day that he would marry his niece Ortensia, as soon as her education was completed. For he was a man of culture and of refined tastes, fond of music, much given to writing sonnets and to reading the works of the elegant Politian, as well as to composing sentimental airs for the voice and lute. He patronised arts and letters with vast credit and secret economy; for he never gave anything more than a supper and a recommendation to the poets, musicians, and artists who paid their court to him and dedicated to him their choicest productions. The supper was generally a frugal affair, but his reputation in æsthetic matters was so great that a word from him to a leader of fashion, or a letter of introduction to a Venetian Ambassador abroad, often proved to be worth more than the gold he abstained from giving. He spoke Latin, he could read Greek, and his taste in poetry was so highly cultivated that he called Dante's verse rough, uncouth, and vulgar—precisely as Horace Walpole, seventy or eighty years later, could not conceive how any one could prefer Shakespeare's rude lines to the elegant verses of Mr. Pope. For the Senator lived in the age when Louis XIV. was young, and Charles II. had been restored to the throne only a few years before the beginning of this story. Pignaver was about fifty years old. There is no good reason why a widower of that age, robust and temperate, and hardly grey, should not take a wife; perhaps there is really no reason, either, why he should not marry a girl of eighteen, if she will have him, and where neither usage nor ecclesiastical ordinances are opposed to it, the young lady may even be his niece. Besides, in the present case, the Senator would appear to his peers and associates to be conferring a favour on the object of his elderly affections, and to be crowning the series of favours he had already conferred. For Ortensia was the penniless child of his brother-in-law, a scapegrace who had come to a bad end in Crete. The Senator's wife had taken the child to her heart, having none of her own, and had brought her up lovingly and wisely, little dreaming that she was educating her own successor. If she had known it, she might have behaved differently, for her lord had never succeeded in winning her affections, and she regarded him to the end with mingled distrust and dislike, while he looked upon her as an affliction and a thorn in his side. Yet they were both very good people in their way. She died comparatively young, and he deemed it only just that after enduring the thorn so long, he should enjoy the rose for the rest of his life. When Ortensia was seventeen and a half her uncle announced his matrimonial intentions to her, fastened a fine string of pearls round her throat, kissed her on the forehead, and left her alone to meditate on her good fortune. Her reflections were of a mixed character, however, and not all pleasant. The idea that she could disobey or resist did not occur to her, of course, for the Senator had always appeared to her as the absolute lord of his household, against whose will it was useless to make any opposition, and she knew what an important person he was considered to be amongst his equals

The Senator Michele Pignaver, being a childless widower of several years' standing and a personage of wealth and worth in Venice, made up his mind one day that he would marry his niece Ortensia, as soon as her education was completed. For he was a man of culture and of refined tastes, fond of music, much given to writing sonnets and to reading the works of the elegant Politian, as well as to composing sentimental airs for the voice and lute. He patronised arts and letters with vast credit and secret economy; for he never gave anything more than a supper and a recommendation to the poets, musicians, and artists who paid their court to him and dedicated to him their choicest productions. The supper was generally a frugal affair, but his reputation in æsthetic matters was so great that a word from him to a leader of fashion, or a letter of introduction to a Venetian Ambassador abroad, often proved to be worth more than the gold he abstained from giving. He spoke Latin, he could read Greek, and his taste in poetry was so highly cultivated that he called Dante's verse rough, uncouth, and vulgar—precisely as Horace Walpole, seventy or eighty years later, could not conceive how any one could prefer Shakespeare's rude lines to the elegant verses of Mr. Pope. For the Senator lived in the age when Louis XIV. was young, and Charles II. had been restored to the throne only a few years before the beginning of this story. Pignaver was about fifty years old. There is no good reason why a widower of that age, robust and temperate, and hardly grey, should not take a wife; perhaps there is really no reason, either, why he should not marry a girl of eighteen, if she will have him, and where neither usage nor ecclesiastical ordinances are opposed to it, the young lady may even be his niece. Besides, in the present case, the Senator would appear to his peers and associates to be conferring a favour on the object of his elderly affections, and to be crowning the series of favours he had already conferred. For Ortensia was the penniless child of his brother-in-law, a scapegrace who had come to a bad end in Crete. The Senator's wife had taken the child to her heart, having none of her own, and had brought her up lovingly and wisely, little dreaming that she was educating her own successor. If she had known it, she might have behaved differently, for her lord had never succeeded in winning her affections, and she regarded him to the end with mingled distrust and dislike, while he looked upon her as an affliction and a thorn in his side. Yet they were both very good people in their way. She died comparatively young, and he deemed it only just that after enduring the thorn so long, he should enjoy the rose for the rest of his life. When Ortensia was seventeen and a half her uncle announced his matrimonial intentions to her, fastened a fine string of pearls round her throat, kissed her on the forehead, and left her alone to meditate on her good fortune. Her reflections were of a mixed character, however, and not all pleasant. The idea that she could disobey or resist did not occur to her, of course, for the Senator had always appeared to her as the absolute lord of his household, against whose will it was useless to make any opposition, and she knew what an important person he was considered to be amongst his equals