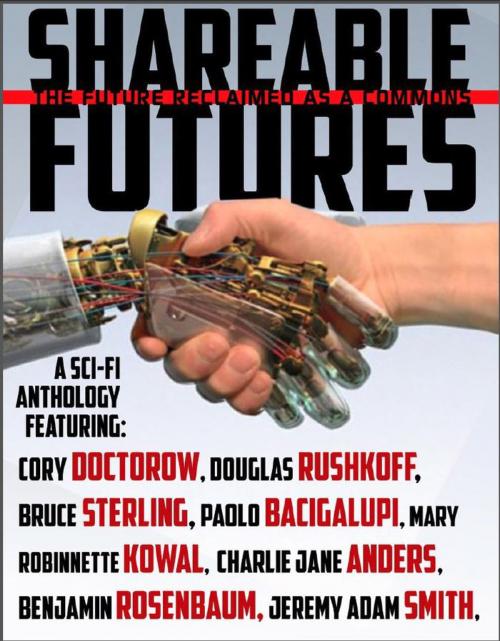

Shareable Futures: The Future Reclaimed as a Commons

Nonfiction, Social & Cultural Studies, Political Science, Social Science| Author: | Shareable Magazine | ISBN: | 9781614645795 |

| Publisher: | Hyperink | Publication: | November 7, 2012 |

| Imprint: | Hyperink | Language: | English |

| Author: | Shareable Magazine |

| ISBN: | 9781614645795 |

| Publisher: | Hyperink |

| Publication: | November 7, 2012 |

| Imprint: | Hyperink |

| Language: | English |

Introducing Shareable Futures

Where our future used to be, we now face a massive debt.

The debt is national and measurable. We in America spent two decades buying on credit. We made promises we couldn’t keep to buy cars, houses, vacations, and plasma screens we couldn’t afford. When we defaulted, the debt shifted upward to a government that had already been putting its wars and occupations on the global equivalent of plastic.

The debt is also environmental and abstract. All this crap we bought on credit had to come out of the earth. We’ve razed forests and eroded soil, over-fished the oceans and depleted fresh water, and turned our bodies and environment into toxic waste dumps. We took oil and coal out of the ground and turned it into smoke that has been trapping heat in the atmosphere.

In short, we consumed like there was no tomorrow. And as a result of the economic and environmental crises triggered by our multi-decade spending spree, tomorrow now seems to be shrinking to a little black dot.

To state the problem in the starkest, most personal terms: I look at my son and I try to imagine the future in which he will live, and I can’t do it. I don’t dare. I don’t believe that I am unique in feeling this way. Too often, when we now look to the future, we face a “Keep Out!” sign propped up by a combination of our own fear and anxiety.

This is another crisis, one that is unfolding on the most intimate and the most public levels. It’s a crisis because we need futurity in the same way that we need air, food, and water—other resources threatened by the forces of enclosure. Not just any futurity, but concepts of the future in which tomorrow is in some way better than today.

To put it another way: We need to know that our actions in the present will count toward something, will be meaningful. Not just a future for our own damn selves, but for the whole of the planet and humanity. The future belongs to everyone, or it should—and, indeed, the future is much more difficult to enclose than other commons. Anyone can access or use the future, through the power of our imaginations.

That's one way of defining “the commons”: anything that no one owns but everyone can access and use. The Internet is a commons. So are the oceans and our atmosphere. The radio spectrum is a commons. So are our streets and water delivery systems.

All of these things require intention and cooperation to maintain, lest we use them up. In other words, all the commons need people to care about them. They need cultivation.

So does the commons we call the future. We don’t cultivate the future with shovels or software, the way we might tend other commons. Instead, we cultivate the commons of the future through stories. The future is, in fact, just a collection of stories that we tell each other. The more and the better stories we tell—and the more people we tell them to—the more we strengthen the commons of the future.

That’s why Shareable.net launched the Shareable Futures series, where some of today's most visionary and accomplished literary futurists imagine futures where technology has changed the rules of ownership and access, and people are able to share transportation, living spaces, lives, dreams, everything and anything. These are futures in which we are surviving and even thriving, largely by learning to share our stuff.

The short stories and speculative essays of the Shareable Futures series are ultimately hopeful, but they are not utopian propaganda; our writers come from the perspective that the laws of social thermodynamics are impossible to escape. Instead of utopia, these stories give readers troubles and ambiguities, vividly conceived characters and places, compelling narratives and intelligent speculation. We hope you’ll enjoy them, and enjoy them in the context of the other, real-life, here-and-now stories we tell on Shareable.net.

Introducing Shareable Futures

Where our future used to be, we now face a massive debt.

The debt is national and measurable. We in America spent two decades buying on credit. We made promises we couldn’t keep to buy cars, houses, vacations, and plasma screens we couldn’t afford. When we defaulted, the debt shifted upward to a government that had already been putting its wars and occupations on the global equivalent of plastic.

The debt is also environmental and abstract. All this crap we bought on credit had to come out of the earth. We’ve razed forests and eroded soil, over-fished the oceans and depleted fresh water, and turned our bodies and environment into toxic waste dumps. We took oil and coal out of the ground and turned it into smoke that has been trapping heat in the atmosphere.

In short, we consumed like there was no tomorrow. And as a result of the economic and environmental crises triggered by our multi-decade spending spree, tomorrow now seems to be shrinking to a little black dot.

To state the problem in the starkest, most personal terms: I look at my son and I try to imagine the future in which he will live, and I can’t do it. I don’t dare. I don’t believe that I am unique in feeling this way. Too often, when we now look to the future, we face a “Keep Out!” sign propped up by a combination of our own fear and anxiety.

This is another crisis, one that is unfolding on the most intimate and the most public levels. It’s a crisis because we need futurity in the same way that we need air, food, and water—other resources threatened by the forces of enclosure. Not just any futurity, but concepts of the future in which tomorrow is in some way better than today.

To put it another way: We need to know that our actions in the present will count toward something, will be meaningful. Not just a future for our own damn selves, but for the whole of the planet and humanity. The future belongs to everyone, or it should—and, indeed, the future is much more difficult to enclose than other commons. Anyone can access or use the future, through the power of our imaginations.

That's one way of defining “the commons”: anything that no one owns but everyone can access and use. The Internet is a commons. So are the oceans and our atmosphere. The radio spectrum is a commons. So are our streets and water delivery systems.

All of these things require intention and cooperation to maintain, lest we use them up. In other words, all the commons need people to care about them. They need cultivation.

So does the commons we call the future. We don’t cultivate the future with shovels or software, the way we might tend other commons. Instead, we cultivate the commons of the future through stories. The future is, in fact, just a collection of stories that we tell each other. The more and the better stories we tell—and the more people we tell them to—the more we strengthen the commons of the future.

That’s why Shareable.net launched the Shareable Futures series, where some of today's most visionary and accomplished literary futurists imagine futures where technology has changed the rules of ownership and access, and people are able to share transportation, living spaces, lives, dreams, everything and anything. These are futures in which we are surviving and even thriving, largely by learning to share our stuff.

The short stories and speculative essays of the Shareable Futures series are ultimately hopeful, but they are not utopian propaganda; our writers come from the perspective that the laws of social thermodynamics are impossible to escape. Instead of utopia, these stories give readers troubles and ambiguities, vividly conceived characters and places, compelling narratives and intelligent speculation. We hope you’ll enjoy them, and enjoy them in the context of the other, real-life, here-and-now stories we tell on Shareable.net.