In the Days of Washington: A Story of The American Revolution

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | William Murray Graydon | ISBN: | 9781465575968 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | William Murray Graydon |

| ISBN: | 9781465575968 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

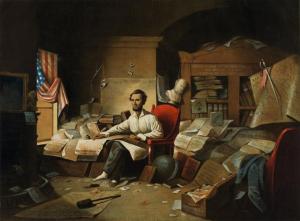

It was an evening in the first week in February, 1778. Supper was over in the house of Cornelius De Vries, which stood on Green Street, Philadelphia, and in that part of the town known as the Northern Liberties. Agatha De Vries, the elderly and maiden sister of Cornelius, had washed and put away the dishes and had gone around the corner to gossip with a neighbor. The light shed from two copper candlesticks and from the fire made the sitting-room look very snug and cozy. In one corner stood a tall clock-case, flanked by a white pine settee and a chest of drawers. A spider legged writing-desk stood near the tile lined fireplace, over which was a row of china dishes—very rare at that time. The floor was white and sanded, and the walls were hung with a few paintings and colored prints. Cornelius De Vries, a well-to-do and retired merchant, occupied a broad-armed chair at one side of the table that stood in the middle of the room. He was a very stately old gentleman of sixty, with a clean-shaven and wrinkled face. He wore a wig, black stockings, a coat and vest of broadcloth, and low shoes with silver buckles. His features betrayed his Dutch origin, as did also the long-stemmed pipe he was smoking, and the glass of Holland schnapps at his elbow. At the opposite side of the table sat Nathan Stanbury, a handsome lad, neatly dressed in gray homespun and starched linen, and of a size and strength that belied his seventeen years. His cheeks were ruddy with health, and his curly chestnut hair matched the deep brown of his eyes. Nathan was a student at the College of Philadelphia, and the open book in his hand was a Latin Horace. But he found it difficult to fix his mind on the lesson, and his thoughts were constantly straying far from the printed pages. Doubtless the wits of Cornelius De Vries were wool-gathering in the same direction, for he had put aside the hated evening paper, "The Royal Gazette," and was dreamily watching the blue curls of smoke as they puffed upward from his pipe. Now he would frown severely, and now his eyes would twinkle and his cheeks distend in a grim sort of smile. There was much for the loyal people of the town to talk and think about at that time. For nearly six months the British army, under General Howe, had occupied Philadelphia in ease and comfort, while at Valley Forge Washington's ragged soldiers were starving and freezing in the wintry weather, their heroic commander bearing in dignified silence the censure and complaint that were freely vented by his countrymen. Black and desperate, indeed, seemed the cause of the United American Colonies in that winter of 1777-78, and as yet no light of cheer was breaking on the horizon.

It was an evening in the first week in February, 1778. Supper was over in the house of Cornelius De Vries, which stood on Green Street, Philadelphia, and in that part of the town known as the Northern Liberties. Agatha De Vries, the elderly and maiden sister of Cornelius, had washed and put away the dishes and had gone around the corner to gossip with a neighbor. The light shed from two copper candlesticks and from the fire made the sitting-room look very snug and cozy. In one corner stood a tall clock-case, flanked by a white pine settee and a chest of drawers. A spider legged writing-desk stood near the tile lined fireplace, over which was a row of china dishes—very rare at that time. The floor was white and sanded, and the walls were hung with a few paintings and colored prints. Cornelius De Vries, a well-to-do and retired merchant, occupied a broad-armed chair at one side of the table that stood in the middle of the room. He was a very stately old gentleman of sixty, with a clean-shaven and wrinkled face. He wore a wig, black stockings, a coat and vest of broadcloth, and low shoes with silver buckles. His features betrayed his Dutch origin, as did also the long-stemmed pipe he was smoking, and the glass of Holland schnapps at his elbow. At the opposite side of the table sat Nathan Stanbury, a handsome lad, neatly dressed in gray homespun and starched linen, and of a size and strength that belied his seventeen years. His cheeks were ruddy with health, and his curly chestnut hair matched the deep brown of his eyes. Nathan was a student at the College of Philadelphia, and the open book in his hand was a Latin Horace. But he found it difficult to fix his mind on the lesson, and his thoughts were constantly straying far from the printed pages. Doubtless the wits of Cornelius De Vries were wool-gathering in the same direction, for he had put aside the hated evening paper, "The Royal Gazette," and was dreamily watching the blue curls of smoke as they puffed upward from his pipe. Now he would frown severely, and now his eyes would twinkle and his cheeks distend in a grim sort of smile. There was much for the loyal people of the town to talk and think about at that time. For nearly six months the British army, under General Howe, had occupied Philadelphia in ease and comfort, while at Valley Forge Washington's ragged soldiers were starving and freezing in the wintry weather, their heroic commander bearing in dignified silence the censure and complaint that were freely vented by his countrymen. Black and desperate, indeed, seemed the cause of the United American Colonies in that winter of 1777-78, and as yet no light of cheer was breaking on the horizon.