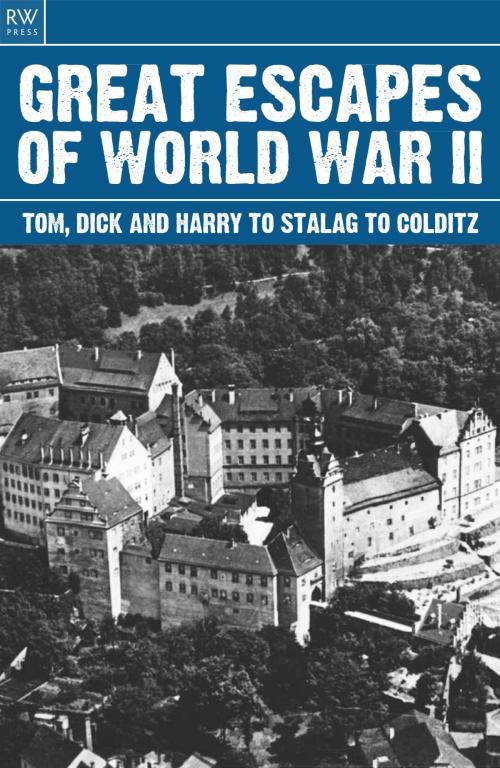

Great Escapes of World War II

Tom Dick and Harry to Stalag to Colditz

Nonfiction, History, Reference, Military, World War II| Author: | Freya Hardy | ISBN: | 9781909284104 |

| Publisher: | RW Press | Publication: | January 10, 2013 |

| Imprint: | RW Press | Language: | English |

| Author: | Freya Hardy |

| ISBN: | 9781909284104 |

| Publisher: | RW Press |

| Publication: | January 10, 2013 |

| Imprint: | RW Press |

| Language: | English |

Great Escapes of World War II

Tom Dick and Harry to Stalag to Colditz

Contents

Introduction; The Laufen Six; Slawomir Rawicz: Hero or Hoaxer?; Airey Neave and Norman Forbes Escape from Thorn; Dulag Luft Tunnel; The Colditz Canteen Tunnel; The Theatre Bust: Airey Neave and Anthony Luteyn; The Medium-Sized Officer; Pat Reid Escapes from Colditz; The Wooden Horse; The Great Escape

More than 170,000 British prisoners of war were taken by German and Italian forces during World War II, enough men to populate modern-day St Lucia. Most were captured in a string of defeats in France, North Africa and the Balkans between 1940 and 1942. They were held in a network of POW camps stretching from Nazi-occupied Poland to Italy. On the whole, the Germans and Italians treated their British prisoners properly, but the rules of the Geneva Convention, set up to govern how POWs should be treated under law, was not always followed and some camps were more hospitable than others. By far the most harmful aspects of incarceration were physical debilitation caused by chronic food shortages, and boredom. Food scarcity was a problem across the board but, to some extent, this could be addressed by the Red Cross, who regularly sent food parcels to men in prison camps. Boredom, however, was a killer. Many prisoners had suddenly gone from being busily engaged in high-adrenalin combat situations to a prison camp, where their identity was stripped away and every aspect of their lives taken out of their control. A small proportion were driven mad. Others became hell-bent on escape.

Hollywood Myth : Hollywood has led us to believe that all our POWs were impassioned escapers. That is utterly untrue. The vast majority of prisoners were too physically weak, through meagre food rations and gruelling hard work, even to contemplate escape. They had already given everything they had to the war effort, and enough was enough. They figured that, if they could sit out the rest of the war in prison, keep their noses clean and their heads down, they may be lucky enough to see their families again. Escape, on the other hand, was a highly dangerous undertaking. Very few successfully made it out of the camp and those who did ran a very real risk of being shot on sight. Often it involved months of hard work followed by long, gruelling journeys through enemy territory with very little or no food. Many who eventually reached a neutral border were so exhausted by the time they got there that they lost concentration and wandered straight back into enemy hands.

Author Biography

Freya Hardy is a freelance writer. She regularly contributes to a number of national and international magazines. She worked as an editor for several publishers for eight years before deciding to view the publishing world from an author’s point of view instead. Fascinated by history she has a particular interest in 20th century history and World War II. She lives with her husband and twin daughters in East Sussex.

Great Escapes of World War II

Tom Dick and Harry to Stalag to Colditz

Contents

Introduction; The Laufen Six; Slawomir Rawicz: Hero or Hoaxer?; Airey Neave and Norman Forbes Escape from Thorn; Dulag Luft Tunnel; The Colditz Canteen Tunnel; The Theatre Bust: Airey Neave and Anthony Luteyn; The Medium-Sized Officer; Pat Reid Escapes from Colditz; The Wooden Horse; The Great Escape

More than 170,000 British prisoners of war were taken by German and Italian forces during World War II, enough men to populate modern-day St Lucia. Most were captured in a string of defeats in France, North Africa and the Balkans between 1940 and 1942. They were held in a network of POW camps stretching from Nazi-occupied Poland to Italy. On the whole, the Germans and Italians treated their British prisoners properly, but the rules of the Geneva Convention, set up to govern how POWs should be treated under law, was not always followed and some camps were more hospitable than others. By far the most harmful aspects of incarceration were physical debilitation caused by chronic food shortages, and boredom. Food scarcity was a problem across the board but, to some extent, this could be addressed by the Red Cross, who regularly sent food parcels to men in prison camps. Boredom, however, was a killer. Many prisoners had suddenly gone from being busily engaged in high-adrenalin combat situations to a prison camp, where their identity was stripped away and every aspect of their lives taken out of their control. A small proportion were driven mad. Others became hell-bent on escape.

Hollywood Myth : Hollywood has led us to believe that all our POWs were impassioned escapers. That is utterly untrue. The vast majority of prisoners were too physically weak, through meagre food rations and gruelling hard work, even to contemplate escape. They had already given everything they had to the war effort, and enough was enough. They figured that, if they could sit out the rest of the war in prison, keep their noses clean and their heads down, they may be lucky enough to see their families again. Escape, on the other hand, was a highly dangerous undertaking. Very few successfully made it out of the camp and those who did ran a very real risk of being shot on sight. Often it involved months of hard work followed by long, gruelling journeys through enemy territory with very little or no food. Many who eventually reached a neutral border were so exhausted by the time they got there that they lost concentration and wandered straight back into enemy hands.

Author Biography

Freya Hardy is a freelance writer. She regularly contributes to a number of national and international magazines. She worked as an editor for several publishers for eight years before deciding to view the publishing world from an author’s point of view instead. Fascinated by history she has a particular interest in 20th century history and World War II. She lives with her husband and twin daughters in East Sussex.