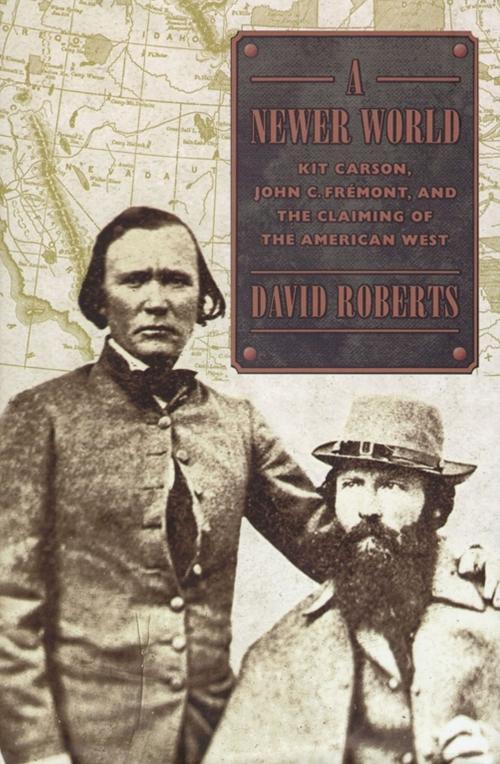

A Newer World

Kit Carson, John C. Fremont and the Claiming of the American West

Nonfiction, History, Americas, United States, 19th Century| Author: | David Roberts | ISBN: | 9780743225762 |

| Publisher: | Simon & Schuster | Publication: | January 10, 2002 |

| Imprint: | Simon & Schuster | Language: | English |

| Author: | David Roberts |

| ISBN: | 9780743225762 |

| Publisher: | Simon & Schuster |

| Publication: | January 10, 2002 |

| Imprint: | Simon & Schuster |

| Language: | English |

John C. Frémont, nearly forgotten today, was one of the giants of nineteenth-century America. He led five expeditions into the American West in the 1840s and 1850s, covering a greater area than any other explorer. His expedition reports -- ghost-written by his beautiful and talented wife, Jessie Benton Frémont -- were bestsellers in their day. Riding the wave of his popularity, he captured the Republican Party nomination for president in 1856 but narrowly lost the election.

Frémont's scout on three of his expeditions was Kit Carson. Frémont fancied himself a mountaineer, and he possessed great stamina and courage, but he lacked Carson's skills and knowledge. The only expedition Frémont led without Carson was a disaster that, like the better-known Donner Party debacle, culminated in one of the rare documented instances of cannibalism in American history.

A Newer World is the fascinating story of the Frémont-Carson expeditions and of two men, utterly unalike in so many ways, who became friends as well as fellow explorers. Frémont owed his life to Carson, who saved him on several occasions, while the legend of Kit Carson, the greatest mountain man of his day, grew out of Frémont's expedition reports. The Frémont-Carson expeditions are second only to Lewis and Clark's in their significance for America's western expansion. Their 1845-46 campaign, for example, helped to precipitate the Mexican-American War and led to the wresting of California from Mexico.

Carson is often remembered today for his 1863-64 roundup of Apaches and Navajos, leading to the infamous Long Walk. David Roberts demonstrates that Carson, who was twice married to Indian women, was profoundly ambivalent about the campaign, which was ordered by an Army officer who was his superior.

Throughout the book, Roberts draws on little-known primary sources in telling the dramatic stories of these expeditions. He shows how Frémont saw himself as a historical figure, especially in his reports, while Carson -- taciturn where Frémont was outspoken, modest where Frémont was boastful, and, significantly, illiterate -- was oblivious to his own fame. Yet it was Carson who underwent an evolution from an Indian killer to an Indian advocate.

In addition to his archival research, Roberts traveled the routes of Frémont and Carson's expeditions to gain a firsthand knowledge of the territory they explored. In analyzing how Frémont and Carson advanced the Americanizing of the West, Roberts writes with a modern-day sensitivity to the Indians, for whom these expeditions were a tragedy.

John C. Frémont, nearly forgotten today, was one of the giants of nineteenth-century America. He led five expeditions into the American West in the 1840s and 1850s, covering a greater area than any other explorer. His expedition reports -- ghost-written by his beautiful and talented wife, Jessie Benton Frémont -- were bestsellers in their day. Riding the wave of his popularity, he captured the Republican Party nomination for president in 1856 but narrowly lost the election.

Frémont's scout on three of his expeditions was Kit Carson. Frémont fancied himself a mountaineer, and he possessed great stamina and courage, but he lacked Carson's skills and knowledge. The only expedition Frémont led without Carson was a disaster that, like the better-known Donner Party debacle, culminated in one of the rare documented instances of cannibalism in American history.

A Newer World is the fascinating story of the Frémont-Carson expeditions and of two men, utterly unalike in so many ways, who became friends as well as fellow explorers. Frémont owed his life to Carson, who saved him on several occasions, while the legend of Kit Carson, the greatest mountain man of his day, grew out of Frémont's expedition reports. The Frémont-Carson expeditions are second only to Lewis and Clark's in their significance for America's western expansion. Their 1845-46 campaign, for example, helped to precipitate the Mexican-American War and led to the wresting of California from Mexico.

Carson is often remembered today for his 1863-64 roundup of Apaches and Navajos, leading to the infamous Long Walk. David Roberts demonstrates that Carson, who was twice married to Indian women, was profoundly ambivalent about the campaign, which was ordered by an Army officer who was his superior.

Throughout the book, Roberts draws on little-known primary sources in telling the dramatic stories of these expeditions. He shows how Frémont saw himself as a historical figure, especially in his reports, while Carson -- taciturn where Frémont was outspoken, modest where Frémont was boastful, and, significantly, illiterate -- was oblivious to his own fame. Yet it was Carson who underwent an evolution from an Indian killer to an Indian advocate.

In addition to his archival research, Roberts traveled the routes of Frémont and Carson's expeditions to gain a firsthand knowledge of the territory they explored. In analyzing how Frémont and Carson advanced the Americanizing of the West, Roberts writes with a modern-day sensitivity to the Indians, for whom these expeditions were a tragedy.