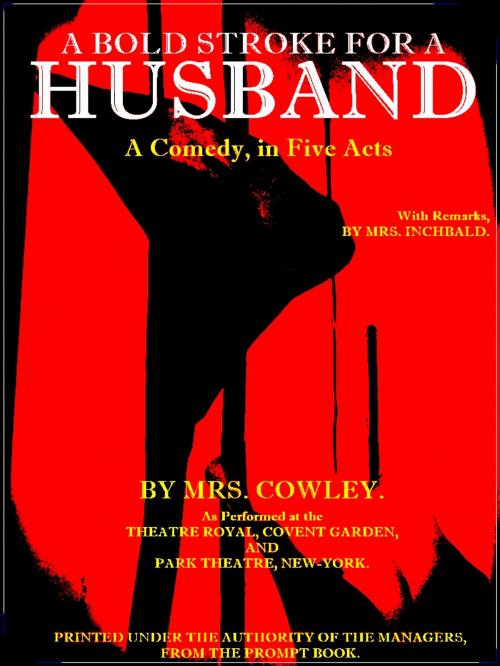

A Bold Stroke for a Husband

A Comedy in Five Acts

Nonfiction, Entertainment, Humour & Comedy, General Humour, Fiction & Literature, Humorous| Author: | Hannah Cowley, Mrs. Inchbald | ISBN: | 1230000287518 |

| Publisher: | E. B. CLAYTON | Publication: | December 23, 2014 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Hannah Cowley, Mrs. Inchbald |

| ISBN: | 1230000287518 |

| Publisher: | E. B. CLAYTON |

| Publication: | December 23, 2014 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

Although "The Bold Stroke for a Husband," by Mrs. Cowley, does not equal "The Bold Stroke for a Wife," by Mrs. Centlivre, either in originality of design, wit, or humour, it has other advantages more honourable to her sex, and more conducive to the reputation of the stage.

Here is contained no oblique insinuation, detrimental to the cause of morality—but entertainment and instruction unite, to make a pleasant exhibition at a theatre, or give an hour's amusement in the closet.

Plays, where the scene is placed in a foreign country, particularly when that country is Spain, have a license to present certain improbabilities to the audience, without incurring the danger of having them called such; and the authoress, by the skill with which she has used this dramatic permittance, in making the wife of Don Carlos pass for a man, has formed a most interesting plot, and embellished it with lively, humorous, and affecting incident.

Still there is another plot, of which Olivia is the heroine, as Victoria is of the foregoing; and this more comic fable, in which the former is chiefly concerned, seems to have been the favourite story of the authoress, as from this she has taken her title.

But if Olivia makes a bold stroke to obtain a husband, surely Victoria makes a still bolder, to preserve one; and there is something less honourable in the enterprises of the young maiden, in order to renounce her state, than in those of a married woman to avert the dangers that are impending over hers.

Whichever of those females becomes the most admired object with the reader, he will not be insensible to the trials of the other, or to the various interests of the whole dramatis personæ, to whom the writer has artfully given a kind of united influence; and upon a happy combination it is, that sometimes, the success of a drama more depends, than upon the most powerful support of any particularly prominent, yet insulated, character.

The part of Don Vincentio was certainly meant as a moral satire upon the extravagant love or the foolish affectation, of pretending to love, to extravagance—music. This satire was aimed at so many, that the shaft struck none. The charm of music still prevails in England, and the folly of affected admirers.

Vincentio talks music, and Don Julio speaks poetry. Such, at least, is his fond description of his mistress Olivia, in that excellent scene in the third act, where she first takes off her veil, and fascinates him at once by the force of her beauty.

In the delineation of this lady, it is implied that she is no termagant, although she so frequently counterfeits the character. This insinuation the reader, if he pleases, may trust—but the man who would venture to marry a good impostor of this kind, could not excite much pity, if his helpmate was often induced to act the part which she had heretofore, with so much spirit, assumed.

The impropriety of making fraud and imposition necessary evils, to counteract tyranny and injustice, is the fault of all Spanish dramas—and perhaps the only one which attaches to the present comedy.

Although "The Bold Stroke for a Husband," by Mrs. Cowley, does not equal "The Bold Stroke for a Wife," by Mrs. Centlivre, either in originality of design, wit, or humour, it has other advantages more honourable to her sex, and more conducive to the reputation of the stage.

Here is contained no oblique insinuation, detrimental to the cause of morality—but entertainment and instruction unite, to make a pleasant exhibition at a theatre, or give an hour's amusement in the closet.

Plays, where the scene is placed in a foreign country, particularly when that country is Spain, have a license to present certain improbabilities to the audience, without incurring the danger of having them called such; and the authoress, by the skill with which she has used this dramatic permittance, in making the wife of Don Carlos pass for a man, has formed a most interesting plot, and embellished it with lively, humorous, and affecting incident.

Still there is another plot, of which Olivia is the heroine, as Victoria is of the foregoing; and this more comic fable, in which the former is chiefly concerned, seems to have been the favourite story of the authoress, as from this she has taken her title.

But if Olivia makes a bold stroke to obtain a husband, surely Victoria makes a still bolder, to preserve one; and there is something less honourable in the enterprises of the young maiden, in order to renounce her state, than in those of a married woman to avert the dangers that are impending over hers.

Whichever of those females becomes the most admired object with the reader, he will not be insensible to the trials of the other, or to the various interests of the whole dramatis personæ, to whom the writer has artfully given a kind of united influence; and upon a happy combination it is, that sometimes, the success of a drama more depends, than upon the most powerful support of any particularly prominent, yet insulated, character.

The part of Don Vincentio was certainly meant as a moral satire upon the extravagant love or the foolish affectation, of pretending to love, to extravagance—music. This satire was aimed at so many, that the shaft struck none. The charm of music still prevails in England, and the folly of affected admirers.

Vincentio talks music, and Don Julio speaks poetry. Such, at least, is his fond description of his mistress Olivia, in that excellent scene in the third act, where she first takes off her veil, and fascinates him at once by the force of her beauty.

In the delineation of this lady, it is implied that she is no termagant, although she so frequently counterfeits the character. This insinuation the reader, if he pleases, may trust—but the man who would venture to marry a good impostor of this kind, could not excite much pity, if his helpmate was often induced to act the part which she had heretofore, with so much spirit, assumed.

The impropriety of making fraud and imposition necessary evils, to counteract tyranny and injustice, is the fault of all Spanish dramas—and perhaps the only one which attaches to the present comedy.

![Cover of the book Tutta colpa degli Occhi Azzurri [completo] by Hannah Cowley, Mrs. Inchbald](https://www.kuoky.com/images/2016/april/300x300/9788892588943-srez_300x.jpg)