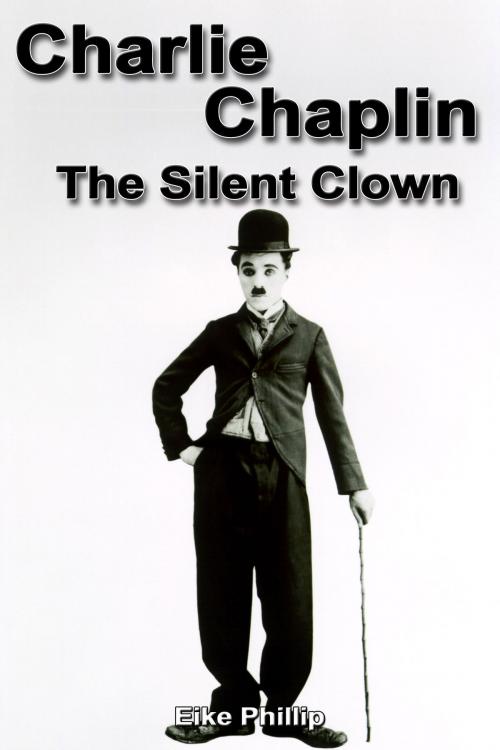

Charlie Chaplin: The Silent Clown

Biography & Memoir, Artists, Architects & Photographers, Nonfiction, Art & Architecture, Entertainment & Performing Arts| Author: | Eike Phillip | ISBN: | 1230000226291 |

| Publisher: | Eike Phillip | Publication: | March 17, 2014 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Eike Phillip |

| ISBN: | 1230000226291 |

| Publisher: | Eike Phillip |

| Publication: | March 17, 2014 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

Film Career

In 1914 Chaplin made his film debut in a somewhat forgettable one-realer called Make a Living. To differentiate himself from the clad of other actors in Sennett films, Chaplin decided to play a single identifiable character. "The Little Tramp" was born, with audiences getting their first taste of him in Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914).

Over the next year, Chaplin appeared in 35 movies, a lineup that included Tillie's Punctured Romance, film's first full-length comedy. In 1915 Chaplin left Sennett to join the Essanay Company, which agreed to pay him $1,250 a week. It's with Essanay that Chaplin, who by this time had hired his brother Sydney to be his business manager, raised to stardom.

During his first year with the company, Chaplin made 14 films, including The Tramp (1915). Generally regarded as the actor's first classic, the story establishes Chaplin's character as unexpected hero when he saves farmer's daughter from a gang of robbers.

By the age of 26, Chaplin, just three years removed from his vaudeville days was a movie superstar. He'd moved over to the Mutual Company, which paid him a whopping $670,000 a year. The money made Chaplin a wealthy man, but it didn't seem to derail his artistic drive. With Mutual, he made some of his best work, including One A.M. (1916), The Rink (1916), The Vagabond (1916), and Easy Street (1917).

Through his work, Chaplin came to be known as a grueling perfectionist. His love for experimentation often meant countless retakes and it was not uncommon for him to order the rebuilding of an entire set. It also wasn't rare for him to begin with one leading actor, realize he'd made a mistake in his casting, and start again with someone new.

But the results were hard to refute. During the 1920s Chaplin's career blossomed even more. During the decade he made some landmark films, including The Kid (1921), The Pilgrim (1923), A Woman in Paris (1923), The Gold Rush (1925), a movie Chaplin would later say he wanted to be remembered by, and The Circus (1928). The latter three were released by United Artists, a company Chaplin co-founded in 1919 with Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and D.W. Griffith.

Off Screen Drama

Chaplin became equally famous for his life off-screen. His affairs with actresses who had roles in his movies were numerous. Some, however, ended better than others.

In 1918 he quickly married 16-year-old Mildred Harris. The marriage lasted two years, and in 1924 he wed again, to another 16-year-old, actress Lita Grey, whom he'd cast in The Gold Rush. The marriage had been brought on by an unplanned pregnancy, and the resulting union, which produced two sons for Chaplin (Charles Jr., and Sydney) was an unhappy one for both partners. The two split in 1927.

In 1936, Chaplin married again, this time to a chorus girl who went by the film name of Paulette Goddard. They lasted until 1942. That was followed by a nasty paternity suit with another actress, Joan Barry, in which tests proved Chaplin was not the father of her daughter but a jury still ordered him to pay child support.

In 1943, Chaplin married 18-year-old Oona O'Neil, the daughter of playwright, Eugene O'Neil. Unexpectedly the two would go on to have a happy marriage, one that would result in eight children for the couple.

Later Films

Chaplin kept creating interesting and engaging films in the 1930s. In 1931, he released City Lights, a critical and commercial success that incorporated music Chaplin scored himself.

More acclaim came with Modern Times (1936), a biting commentary about the state of world's economic and political infrastructures. The film, which did incorporate sound and did not include "The Little Tramp" character, was, in part, the result of an 18-month world tour Chaplin had taken between 1931 and 1932, a trip in which he'd witnessed severe economic angst and a sharp rise in nationalism in Europe and elsewhere.

Chaplin spoke even louder in The Great Dictator (1940), which pointedly ridiculed the governments of Hitler and Mussolini. "I want to see the return of decency and kindness," Chaplin said around the time of the film's release. "I'm just a human being who wants to see this country a real democracy . . ."

But Chaplin was not universally embraced. His romantic liaisons led to his rebuke by some women's groups, which in turn led to him being barred from entering some U.S. states. As the Cold War age settled into existence, Chaplin didn't withhold his fire from injustices he saw taking place in the name of fighting Communism in his adopted country of the United States.

Chaplin soon became a target of the right wing conservatives. Representative John E. Ranking of Mississippi pushed for his deportation. In 1952, the Attorney General of the United States obliged when he announced that Chaplin, who was sailing to Britain on vacation, was not permitted to return to the United States unless he could prove "moral worth." The incensed Chaplin said goodbye to United States and took up residence on a small farm in Vevey, Switzerland.

Final Years

Nearing the end of his life, Chaplin did make one last return to visit to the United States in 1972, when he was awarded a special Academy Award from the Motion Picture Academy. The trip came just six years after Chaplin's final film, A Countess from Hong Kong (1966), the filmmaker's first and only color movie. Despite a cast that included Sophia Loren and Marlon Brando, the film did poorly at the box office. In 1975, Chaplin received more recognition when Queen Elizabeth knighted him.

In the early morning hours of December 25, 1977, Charlie Chaplin died at his home in Corsier-sur-Vevey, Vaud, Switzerland. His wife Oona and seven of his children were at his bedside at the time of his passing. In a twist that might very well have come out of one of his films, Chaplin's body was stolen not long after he was buried from his grave near Lake Geneva in Switzerland by two men who demanded $400,000 for its return. The men were arrested and Chaplin's body was recovered 11 weeks later.

1952: Charlie Chaplin Banned From the US

September 1952 marked Charlie Chaplin's first visit to England in 21 years; yet it also marked the beginning of his exile from the United States. The trip to Europe was meant to be a brief one to promote his new film Limelight, with Chaplin remarking upon his departure that "I shall probably be away for six months, but no more." However, on 19 September, while Chaplin was still at sea, the US Attorney-General announced plans to lauch an inquiry into whether he would be re-admitted to the US. In the end it would be 20 years before he would return.

US press such as the New York Times cautioned that "those who have followed him through the years cannot easily regard him as a dangerous person"; but, as the above article reporting from a press conference given by Chaplin at Cherbourg on 22 September details, American critics of Chaplin's "anti-Americanness' had been following him since 1917.

Chaplin arrived in Southampton on 23 September to a rapturous greeting from fans and well-wishers, and later that day gave a press conference in London where he resolutely stated that he was not a Communist, but someone "who wants nothing more for humanity than a roof over every man's head."

Filming Modern Times

Modern Times marked the last screen appearance of the Little Tramp - the character which had brought Charles Chaplin world fame, and who still remains the most universally recognized fictional image of a human being in the history of art.

The world from which the Tramp took his farewell was very different from that into which he had been born, two decades earlier, before the First World War. Then he had shared and symbolized the hardships of all the underprivileged of a world only just emerging from the 19th century. Modern Times found him facing very different predicaments in the aftermath of America¹s Great Depression, when mass unemployment coincided with the massive rise of industrial automation.

Chaplin was acutely preoccupied with the social and economic problems of this new age. In 1931 and 1932 he had left Hollywood behind, to embark on an 18-month world tour. In Europe, he had been disturbed to see the rise of nationalism and the social effects of the Depression, of unemployment and of automation. He read books on economic theory; and devised his own Economic Solution, an intelligent exercise in utopian idealism, based on a more equitable distribution not just of wealth but of work. In 1931 he told a newspaper interviewer:

bq. “Unemployment is the vital question … Machinery should benefit mankind. It should not spell tragedy and throw it out of work.”

In Modern Times he set out to transform his observations and anxieties into comedy. The little Tramp - described in the film credits as “a Factory Worker”- is now one of the millions coping with the problems of the 1930s, which are not so very different from anxieties of the 21st century - poverty, unemployment, strikes and strike breakers, political intolerance, economic inequalities, the tyranny of the machine, narcotics. The film’s portentous opening title - “The story of industry, of individual enterprise - humanity crusading in the pursuit of happiness” - is followed by a symbolic juxtaposition of shots of sheep being herded and of workers streaming out of a factory. Chaplin’s character is first seen as a worker being driven crazy by his monotonous, inhuman work on a conveyor belt and being used as a guinea pig to test a machine to feed workers as they work.

Paulette Godard

Exceptionally, the Tramp has a companion in his battle with this new world. On his return to America after a world tour in 1931, Chaplin had met the actress Paulette Goddard, who was to remain, for several years, an ideal partner in his private life. Her personality inspired the character of the “Gamine” in Modern Times - a young girl whose father has been killed in a labor demonstration, and who joins forces with Chaplin. The couple are neither rebels nor victims, but, wrote Chaplin, ”The only two live spirits in a world of automatons. We are children with no sense of responsibility, whereas the rest of humanity is weighed down with duty. We are spiritually free”. In a sense, then, they are anarchists.

Chaplin at first planned a sadly sentimental ending for the film. While the Tramp was in hospital, recovering from nervous break-down, the Gamine was to become a Nun and so be parted from him forever. This ending was filmed, but was finally abandoned in favor of a more cheerful finale. “We¹ll get along”, says a title; and the couple, arm in arm, set bravely off down a country lane, towards the horizon.

By the time Modern Times was released, talking pictures had been established for almost a decade. Till now, Chaplin had resisted dialogue, knowing that his comedy and its universal understanding depended on silent pantomime. This time though he weakened to the extent of preparing dialogue, and even doing some trial recordings. Finally he thought better of it, and as in City Lights uses only music and sound effects. Human voices are only heard filtered through technological devices - the boss who addresses his workers from a television screen; the salesman who is only a voice on the phonograph.

Just at one moment, though, Chaplin’s own voice is heard directly. Hired as a waiter, the Little Worker is required to stand in for the romantic café tenor. He writes the words on his shirt cuffs, but these fly off with a too-dramatic flourish; and he is obliged to improvise the song in a wonderful, mock-Italian gibberish. Chaplin’s voice had already been heard on radio and in at least one newsreel, but this was the first and only time that the world heard speech from the Little Tramp.

Apart from this indecision over sound and the changed ending, the shooting seems to have been fairly untroubled and, by Chaplin¹s standards, comparatively fast. It may have helped that the essential structure is neatly devised in four “acts” each one more or less equivalent to one of his old two-reel comedies. As the contemporary American critic Otis Ferguson wrote, they might have been individually titled The Shop, The Jailbird, The Watchman and The Singing Waiter.

Film Career

In 1914 Chaplin made his film debut in a somewhat forgettable one-realer called Make a Living. To differentiate himself from the clad of other actors in Sennett films, Chaplin decided to play a single identifiable character. "The Little Tramp" was born, with audiences getting their first taste of him in Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914).

Over the next year, Chaplin appeared in 35 movies, a lineup that included Tillie's Punctured Romance, film's first full-length comedy. In 1915 Chaplin left Sennett to join the Essanay Company, which agreed to pay him $1,250 a week. It's with Essanay that Chaplin, who by this time had hired his brother Sydney to be his business manager, raised to stardom.

During his first year with the company, Chaplin made 14 films, including The Tramp (1915). Generally regarded as the actor's first classic, the story establishes Chaplin's character as unexpected hero when he saves farmer's daughter from a gang of robbers.

By the age of 26, Chaplin, just three years removed from his vaudeville days was a movie superstar. He'd moved over to the Mutual Company, which paid him a whopping $670,000 a year. The money made Chaplin a wealthy man, but it didn't seem to derail his artistic drive. With Mutual, he made some of his best work, including One A.M. (1916), The Rink (1916), The Vagabond (1916), and Easy Street (1917).

Through his work, Chaplin came to be known as a grueling perfectionist. His love for experimentation often meant countless retakes and it was not uncommon for him to order the rebuilding of an entire set. It also wasn't rare for him to begin with one leading actor, realize he'd made a mistake in his casting, and start again with someone new.

But the results were hard to refute. During the 1920s Chaplin's career blossomed even more. During the decade he made some landmark films, including The Kid (1921), The Pilgrim (1923), A Woman in Paris (1923), The Gold Rush (1925), a movie Chaplin would later say he wanted to be remembered by, and The Circus (1928). The latter three were released by United Artists, a company Chaplin co-founded in 1919 with Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, and D.W. Griffith.

Off Screen Drama

Chaplin became equally famous for his life off-screen. His affairs with actresses who had roles in his movies were numerous. Some, however, ended better than others.

In 1918 he quickly married 16-year-old Mildred Harris. The marriage lasted two years, and in 1924 he wed again, to another 16-year-old, actress Lita Grey, whom he'd cast in The Gold Rush. The marriage had been brought on by an unplanned pregnancy, and the resulting union, which produced two sons for Chaplin (Charles Jr., and Sydney) was an unhappy one for both partners. The two split in 1927.

In 1936, Chaplin married again, this time to a chorus girl who went by the film name of Paulette Goddard. They lasted until 1942. That was followed by a nasty paternity suit with another actress, Joan Barry, in which tests proved Chaplin was not the father of her daughter but a jury still ordered him to pay child support.

In 1943, Chaplin married 18-year-old Oona O'Neil, the daughter of playwright, Eugene O'Neil. Unexpectedly the two would go on to have a happy marriage, one that would result in eight children for the couple.

Later Films

Chaplin kept creating interesting and engaging films in the 1930s. In 1931, he released City Lights, a critical and commercial success that incorporated music Chaplin scored himself.

More acclaim came with Modern Times (1936), a biting commentary about the state of world's economic and political infrastructures. The film, which did incorporate sound and did not include "The Little Tramp" character, was, in part, the result of an 18-month world tour Chaplin had taken between 1931 and 1932, a trip in which he'd witnessed severe economic angst and a sharp rise in nationalism in Europe and elsewhere.

Chaplin spoke even louder in The Great Dictator (1940), which pointedly ridiculed the governments of Hitler and Mussolini. "I want to see the return of decency and kindness," Chaplin said around the time of the film's release. "I'm just a human being who wants to see this country a real democracy . . ."

But Chaplin was not universally embraced. His romantic liaisons led to his rebuke by some women's groups, which in turn led to him being barred from entering some U.S. states. As the Cold War age settled into existence, Chaplin didn't withhold his fire from injustices he saw taking place in the name of fighting Communism in his adopted country of the United States.

Chaplin soon became a target of the right wing conservatives. Representative John E. Ranking of Mississippi pushed for his deportation. In 1952, the Attorney General of the United States obliged when he announced that Chaplin, who was sailing to Britain on vacation, was not permitted to return to the United States unless he could prove "moral worth." The incensed Chaplin said goodbye to United States and took up residence on a small farm in Vevey, Switzerland.

Final Years

Nearing the end of his life, Chaplin did make one last return to visit to the United States in 1972, when he was awarded a special Academy Award from the Motion Picture Academy. The trip came just six years after Chaplin's final film, A Countess from Hong Kong (1966), the filmmaker's first and only color movie. Despite a cast that included Sophia Loren and Marlon Brando, the film did poorly at the box office. In 1975, Chaplin received more recognition when Queen Elizabeth knighted him.

In the early morning hours of December 25, 1977, Charlie Chaplin died at his home in Corsier-sur-Vevey, Vaud, Switzerland. His wife Oona and seven of his children were at his bedside at the time of his passing. In a twist that might very well have come out of one of his films, Chaplin's body was stolen not long after he was buried from his grave near Lake Geneva in Switzerland by two men who demanded $400,000 for its return. The men were arrested and Chaplin's body was recovered 11 weeks later.

1952: Charlie Chaplin Banned From the US

September 1952 marked Charlie Chaplin's first visit to England in 21 years; yet it also marked the beginning of his exile from the United States. The trip to Europe was meant to be a brief one to promote his new film Limelight, with Chaplin remarking upon his departure that "I shall probably be away for six months, but no more." However, on 19 September, while Chaplin was still at sea, the US Attorney-General announced plans to lauch an inquiry into whether he would be re-admitted to the US. In the end it would be 20 years before he would return.

US press such as the New York Times cautioned that "those who have followed him through the years cannot easily regard him as a dangerous person"; but, as the above article reporting from a press conference given by Chaplin at Cherbourg on 22 September details, American critics of Chaplin's "anti-Americanness' had been following him since 1917.

Chaplin arrived in Southampton on 23 September to a rapturous greeting from fans and well-wishers, and later that day gave a press conference in London where he resolutely stated that he was not a Communist, but someone "who wants nothing more for humanity than a roof over every man's head."

Filming Modern Times

Modern Times marked the last screen appearance of the Little Tramp - the character which had brought Charles Chaplin world fame, and who still remains the most universally recognized fictional image of a human being in the history of art.

The world from which the Tramp took his farewell was very different from that into which he had been born, two decades earlier, before the First World War. Then he had shared and symbolized the hardships of all the underprivileged of a world only just emerging from the 19th century. Modern Times found him facing very different predicaments in the aftermath of America¹s Great Depression, when mass unemployment coincided with the massive rise of industrial automation.

Chaplin was acutely preoccupied with the social and economic problems of this new age. In 1931 and 1932 he had left Hollywood behind, to embark on an 18-month world tour. In Europe, he had been disturbed to see the rise of nationalism and the social effects of the Depression, of unemployment and of automation. He read books on economic theory; and devised his own Economic Solution, an intelligent exercise in utopian idealism, based on a more equitable distribution not just of wealth but of work. In 1931 he told a newspaper interviewer:

bq. “Unemployment is the vital question … Machinery should benefit mankind. It should not spell tragedy and throw it out of work.”

In Modern Times he set out to transform his observations and anxieties into comedy. The little Tramp - described in the film credits as “a Factory Worker”- is now one of the millions coping with the problems of the 1930s, which are not so very different from anxieties of the 21st century - poverty, unemployment, strikes and strike breakers, political intolerance, economic inequalities, the tyranny of the machine, narcotics. The film’s portentous opening title - “The story of industry, of individual enterprise - humanity crusading in the pursuit of happiness” - is followed by a symbolic juxtaposition of shots of sheep being herded and of workers streaming out of a factory. Chaplin’s character is first seen as a worker being driven crazy by his monotonous, inhuman work on a conveyor belt and being used as a guinea pig to test a machine to feed workers as they work.

Paulette Godard

Exceptionally, the Tramp has a companion in his battle with this new world. On his return to America after a world tour in 1931, Chaplin had met the actress Paulette Goddard, who was to remain, for several years, an ideal partner in his private life. Her personality inspired the character of the “Gamine” in Modern Times - a young girl whose father has been killed in a labor demonstration, and who joins forces with Chaplin. The couple are neither rebels nor victims, but, wrote Chaplin, ”The only two live spirits in a world of automatons. We are children with no sense of responsibility, whereas the rest of humanity is weighed down with duty. We are spiritually free”. In a sense, then, they are anarchists.

Chaplin at first planned a sadly sentimental ending for the film. While the Tramp was in hospital, recovering from nervous break-down, the Gamine was to become a Nun and so be parted from him forever. This ending was filmed, but was finally abandoned in favor of a more cheerful finale. “We¹ll get along”, says a title; and the couple, arm in arm, set bravely off down a country lane, towards the horizon.

By the time Modern Times was released, talking pictures had been established for almost a decade. Till now, Chaplin had resisted dialogue, knowing that his comedy and its universal understanding depended on silent pantomime. This time though he weakened to the extent of preparing dialogue, and even doing some trial recordings. Finally he thought better of it, and as in City Lights uses only music and sound effects. Human voices are only heard filtered through technological devices - the boss who addresses his workers from a television screen; the salesman who is only a voice on the phonograph.

Just at one moment, though, Chaplin’s own voice is heard directly. Hired as a waiter, the Little Worker is required to stand in for the romantic café tenor. He writes the words on his shirt cuffs, but these fly off with a too-dramatic flourish; and he is obliged to improvise the song in a wonderful, mock-Italian gibberish. Chaplin’s voice had already been heard on radio and in at least one newsreel, but this was the first and only time that the world heard speech from the Little Tramp.

Apart from this indecision over sound and the changed ending, the shooting seems to have been fairly untroubled and, by Chaplin¹s standards, comparatively fast. It may have helped that the essential structure is neatly devised in four “acts” each one more or less equivalent to one of his old two-reel comedies. As the contemporary American critic Otis Ferguson wrote, they might have been individually titled The Shop, The Jailbird, The Watchman and The Singing Waiter.