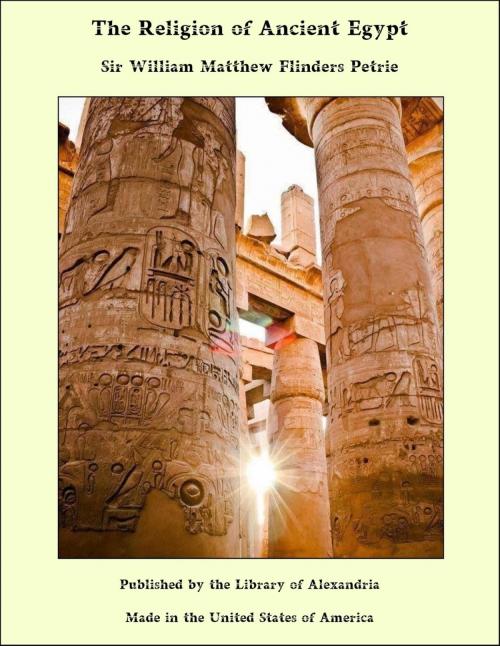

The Religion of Ancient Egypt

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie | ISBN: | 9781613106167 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie |

| ISBN: | 9781613106167 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

Before dealing with the special varieties of the Egyptians' belief in gods, it is best to try to avoid a misunderstanding of their whole conception of the supernatural. The term god has come to tacitly imply to our minds such a highly specialised group of attributes, that we can hardly throw our ideas back into the more remote conceptions to which we also attach the same name. It is unfortunate that every other word for supernatural intelligences has become debased, so that we cannot well speak of demons, devils, ghosts, or fairies without implying a noxious or a trifling meaning, quite unsuited to the ancient deities that were so beneficent and powerful. If then we use the word god for such conceptions, it must always be with the reservation that the word has now a very different meaning from what it had to ancient minds. To the Egyptian the gods might be mortal; even Ra, the sun-god, is said to have grown old and feeble, Osiris was slain, and Orion, the great hunter of the heavens, killed and ate the gods. The mortality of gods has been dwelt on by Dr. Frazer (Golden Bough), and the many instances of tombs of gods, and of the slaying of the deified man who was worshipped, all show that immortality was not a divine attribute. Nor was there any doubt that they might suffer while alive; one myth tells how Ra, as he walked on earth, was bitten by a magic serpent and suffered torments. The gods were also supposed to share in a life like that of man, not only in Egypt but in most ancient lands. Offerings of food and drink were constantly supplied to them, in Egypt laid upon the altars, in other lands burnt for a sweet savour. At Thebes the divine wife of the god, or high priestess, was the head of the harem of concubines of the god; and similarly in Babylonia the chamber of the god with the golden couch could only be visited by the priestess who slept there for oracular responses. The Egyptian gods could not be cognisant of what passed on earth without being informed, nor could they reveal their will at a distant place except by sending a messenger; they were as limited as the Greek gods who required the aid of Iris to communicate one with another or with mankind. The gods, therefore, have no divine superiority to man in conditions or limitations; they can only be described as pre-existent, acting intelligences, with scarcely greater powers than man might hope to gain by magic or witchcraft of his own. This conception explains how easily the divine merged into the human in Greek theology, and how frequently divine ancestors occurred in family histories.

Before dealing with the special varieties of the Egyptians' belief in gods, it is best to try to avoid a misunderstanding of their whole conception of the supernatural. The term god has come to tacitly imply to our minds such a highly specialised group of attributes, that we can hardly throw our ideas back into the more remote conceptions to which we also attach the same name. It is unfortunate that every other word for supernatural intelligences has become debased, so that we cannot well speak of demons, devils, ghosts, or fairies without implying a noxious or a trifling meaning, quite unsuited to the ancient deities that were so beneficent and powerful. If then we use the word god for such conceptions, it must always be with the reservation that the word has now a very different meaning from what it had to ancient minds. To the Egyptian the gods might be mortal; even Ra, the sun-god, is said to have grown old and feeble, Osiris was slain, and Orion, the great hunter of the heavens, killed and ate the gods. The mortality of gods has been dwelt on by Dr. Frazer (Golden Bough), and the many instances of tombs of gods, and of the slaying of the deified man who was worshipped, all show that immortality was not a divine attribute. Nor was there any doubt that they might suffer while alive; one myth tells how Ra, as he walked on earth, was bitten by a magic serpent and suffered torments. The gods were also supposed to share in a life like that of man, not only in Egypt but in most ancient lands. Offerings of food and drink were constantly supplied to them, in Egypt laid upon the altars, in other lands burnt for a sweet savour. At Thebes the divine wife of the god, or high priestess, was the head of the harem of concubines of the god; and similarly in Babylonia the chamber of the god with the golden couch could only be visited by the priestess who slept there for oracular responses. The Egyptian gods could not be cognisant of what passed on earth without being informed, nor could they reveal their will at a distant place except by sending a messenger; they were as limited as the Greek gods who required the aid of Iris to communicate one with another or with mankind. The gods, therefore, have no divine superiority to man in conditions or limitations; they can only be described as pre-existent, acting intelligences, with scarcely greater powers than man might hope to gain by magic or witchcraft of his own. This conception explains how easily the divine merged into the human in Greek theology, and how frequently divine ancestors occurred in family histories.