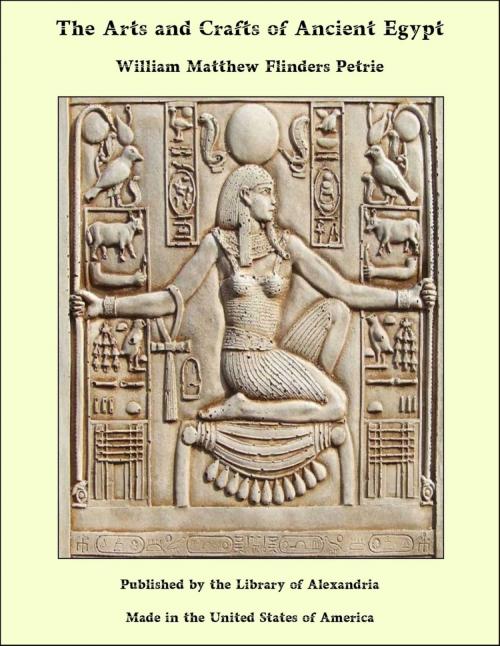

The Arts and Crafts of Ancient Egypt

Nonfiction, Religion & Spirituality, New Age, History, Fiction & Literature| Author: | William Matthew Flinders Petrie | ISBN: | 9781465594662 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria | Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | William Matthew Flinders Petrie |

| ISBN: | 9781465594662 |

| Publisher: | Library of Alexandria |

| Publication: | March 8, 2015 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

The art of a country, like the character of the inhabitants, belongs to the nature of the land. The climate, the scenery, the contrasts of each country, all clothe the artistic impulse as diversely as they clothe the people themselves. A burly, florid Teuton in his furs and jewellery, and a lithe brown Indian in his waist-cloth, would each look entirely absurd in the other’s dress. There is no question of which dress is intrinsically the best in the world; each is relatively the best for its own conditions, and each is out of place in other conditions. So it is with art: it is the expression of thought and feeling in harmony with its own conditions. The only bad art is that which is mechanical, where the impulse to give expression has decayed, and it is reduced to mere copying of styles and motives which do not belong to its actual conditions. An age of copying is the only despicable age. It is but a confusion of thought, therefore, to try to pit the art of one country against that of another. A Corinthian temple, a Norman church, or a Chinese pavilion are each perfect in their own conditions; but if the temple is of Aberdeen granite, the church of Pacific island coral, and the pavilion amid the Brighton downs, they are each of them hopelessly wrong. To understand any art we must first begin by grasping its conditions, and feeling the contrasts, the necessities, the atmosphere, which underlie the whole terms of expression. Now the essential conditions in Egypt are before all, an overwhelming sunshine; next, the strongest of contrasts between a vast sterility of desert and the most prolific verdure of the narrow plain; and thirdly, the illimitable level lines of the cultivation, of the desert plateau, and of the limestone strata, crossed by the vertical precipices on either hand rising hundreds of feet without a break. In such conditions the architecture of other lands would look weak or tawdry. But the style of Egypt never fails in all its varieties and changes.

The art of a country, like the character of the inhabitants, belongs to the nature of the land. The climate, the scenery, the contrasts of each country, all clothe the artistic impulse as diversely as they clothe the people themselves. A burly, florid Teuton in his furs and jewellery, and a lithe brown Indian in his waist-cloth, would each look entirely absurd in the other’s dress. There is no question of which dress is intrinsically the best in the world; each is relatively the best for its own conditions, and each is out of place in other conditions. So it is with art: it is the expression of thought and feeling in harmony with its own conditions. The only bad art is that which is mechanical, where the impulse to give expression has decayed, and it is reduced to mere copying of styles and motives which do not belong to its actual conditions. An age of copying is the only despicable age. It is but a confusion of thought, therefore, to try to pit the art of one country against that of another. A Corinthian temple, a Norman church, or a Chinese pavilion are each perfect in their own conditions; but if the temple is of Aberdeen granite, the church of Pacific island coral, and the pavilion amid the Brighton downs, they are each of them hopelessly wrong. To understand any art we must first begin by grasping its conditions, and feeling the contrasts, the necessities, the atmosphere, which underlie the whole terms of expression. Now the essential conditions in Egypt are before all, an overwhelming sunshine; next, the strongest of contrasts between a vast sterility of desert and the most prolific verdure of the narrow plain; and thirdly, the illimitable level lines of the cultivation, of the desert plateau, and of the limestone strata, crossed by the vertical precipices on either hand rising hundreds of feet without a break. In such conditions the architecture of other lands would look weak or tawdry. But the style of Egypt never fails in all its varieties and changes.