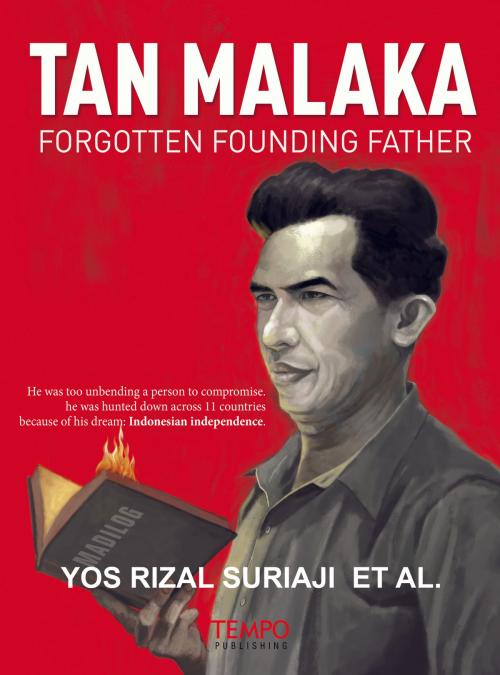

| Author: | Yos Rizal Suriaji et al. | ISBN: | 9781301282807 |

| Publisher: | Tempo Publishing | Publication: | August 21, 2013 |

| Imprint: | Smashwords Edition | Language: | English |

| Author: | Yos Rizal Suriaji et al. |

| ISBN: | 9781301282807 |

| Publisher: | Tempo Publishing |

| Publication: | August 21, 2013 |

| Imprint: | Smashwords Edition |

| Language: | English |

He was too unbending a person to compromise. Wanted by the Dutch, British, American and Japanese secret police, he was hunted down across 11 countries because of his dream: Indonesian independence.

He is Tan Malaka, the first man to conceive the idea of a Republic of Indonesia. Muhammad Yamin named him the real “Father of the Republic of Indonesia.” Sukarno called him “an expert at waging a revolution.” But his was a tragic life, which ended by the guns of an army of the republic he helped create.

HE was a man who set Indonesian revolution in motion: Ibrahim Datuk Tan Malaka, simply known as Tan Malaka. Today, two or three generations of Indonesians might have forgotten this man, who was rich in political ideas and good at organizing.

The New Order tried to erase his name and his role in Indonesian history. But in the eyes of young Indonesians Tan possesses an irresistible attraction. When Suharto was in power delving into Tan’s political thinking was tantamount to reading Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s novels. Books that he wrote were distributed through a clandestine network, his ideas discussed in whispers. Although he clashed with the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), Tan was frequently associated with the PKI, the mortal enemy of the New Order.

Sukarno also treated him in a similar way. For two years he was imprisoned by Sukarno, through the Sjahrir government, without any charges. His conflict with the PKI leadership led to his ouster from the circle of power. When PKI was close to those in power, Sukarno chose Muso, who vowed to hang him for challenging the leadership, over Tan. Dipa Negara Aidit beat the bush trying to find a political testament said to have been written by Sukarno and given to Tan, which transferred leadership of the nation to four people named in the document, including Tan, in the event of Sukarno’s and Hatta’s death or capture by the enemy.

Ironically, Sukarno later burnt the testament which read: “In the event of my death, leadership of the revolution is to be transferred to Tan Malaka, an expert at waging a revolution.”

Politics eventually erased Tan from memory. In Bukittinggi, his birthplace, his name is known vaguely to most of the people there. When Harry Albert Poeze, a Dutch historian researching Tan for the past 36 years, visited Senior High School No. 2 in Bukittinggi last February, teachers there were surprised to learn that Tan studied from 1908-1913 at what was then known as Kweekschool, a teacher training institution. They knew about it only from their students, who browsed the Internet for information. The teachers were not entirely sure until a search of the records carried out after the arrival of Poeze, found in the school cupboard, an inscription bearing the name of one Engku Nawawi Sutan Makmur as a teacher at the time Tan was a student at the school.

He was too unbending a person to compromise. Wanted by the Dutch, British, American and Japanese secret police, he was hunted down across 11 countries because of his dream: Indonesian independence.

He is Tan Malaka, the first man to conceive the idea of a Republic of Indonesia. Muhammad Yamin named him the real “Father of the Republic of Indonesia.” Sukarno called him “an expert at waging a revolution.” But his was a tragic life, which ended by the guns of an army of the republic he helped create.

HE was a man who set Indonesian revolution in motion: Ibrahim Datuk Tan Malaka, simply known as Tan Malaka. Today, two or three generations of Indonesians might have forgotten this man, who was rich in political ideas and good at organizing.

The New Order tried to erase his name and his role in Indonesian history. But in the eyes of young Indonesians Tan possesses an irresistible attraction. When Suharto was in power delving into Tan’s political thinking was tantamount to reading Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s novels. Books that he wrote were distributed through a clandestine network, his ideas discussed in whispers. Although he clashed with the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), Tan was frequently associated with the PKI, the mortal enemy of the New Order.

Sukarno also treated him in a similar way. For two years he was imprisoned by Sukarno, through the Sjahrir government, without any charges. His conflict with the PKI leadership led to his ouster from the circle of power. When PKI was close to those in power, Sukarno chose Muso, who vowed to hang him for challenging the leadership, over Tan. Dipa Negara Aidit beat the bush trying to find a political testament said to have been written by Sukarno and given to Tan, which transferred leadership of the nation to four people named in the document, including Tan, in the event of Sukarno’s and Hatta’s death or capture by the enemy.

Ironically, Sukarno later burnt the testament which read: “In the event of my death, leadership of the revolution is to be transferred to Tan Malaka, an expert at waging a revolution.”

Politics eventually erased Tan from memory. In Bukittinggi, his birthplace, his name is known vaguely to most of the people there. When Harry Albert Poeze, a Dutch historian researching Tan for the past 36 years, visited Senior High School No. 2 in Bukittinggi last February, teachers there were surprised to learn that Tan studied from 1908-1913 at what was then known as Kweekschool, a teacher training institution. They knew about it only from their students, who browsed the Internet for information. The teachers were not entirely sure until a search of the records carried out after the arrival of Poeze, found in the school cupboard, an inscription bearing the name of one Engku Nawawi Sutan Makmur as a teacher at the time Tan was a student at the school.