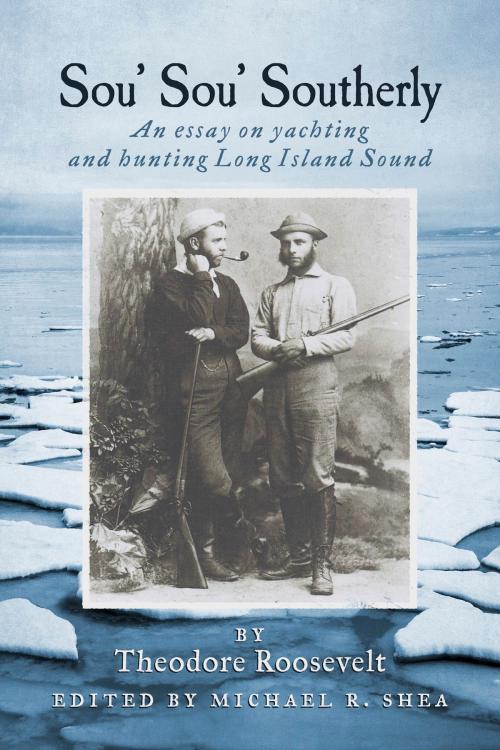

Sou’ Sou’ Southerly (Annotated)

An Essay on Yachting and Hunting Long Island Sound

Nonfiction, History, Americas, United States| Author: | Theodore Roosevelt | ISBN: | 9781483542508 |

| Publisher: | BookBaby | Publication: | November 10, 2014 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Theodore Roosevelt |

| ISBN: | 9781483542508 |

| Publisher: | BookBaby |

| Publication: | November 10, 2014 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

A 22-year-old Theodore Roosevelt first spotted the ducks as black specks on the horizon as his small sloop passed the mouth of the bay. Elliott, his younger brother, worked the tiller, fighting to keep the sails full as they pushed down on the birds. T.R. sat forward in the ready, shotgun in hand. The birds rafted tight together as the boat approached before “an old ‘pigeon tail’ took the alarm and rose,” T.R. would later write. He picked up his own gun, “and just as the great clump of birds ahead of us got fairly started at about thirty yards off we put all four barrels of no. 4 shot into them, and as we swept down through the flock put in four barrels more. The boat was left to herself and broached to; hauling in the sheets, one of us rushed to the bow with a long-handled scoop net, to pick up the birds. There were so many feathers floating on the water that it looked as if a pillow had burst over it.” The year 1880 was a busy one for Young Roosevelt. In March a doctor advised him against “the strenuous life” after diagnosing a heart condition on top of his chronic asthma. A few months later he graduated from Harvard magma cum laude, then took a trip to the Maine coast before a long upland hunt for grouse and prairie chicken in the upper Midwest. Back in the northeast that fall, he enrolled in Columbia Law School, married his first wife Alice Hathaway Lee in October, and was writing the final chapters in what would be his first book, The Naval War of 1812. Yet it was his duck hunt and sailing adventure on Long Island Sound he chose to memorialize that year in a short essay titled Sou’ Sou’ Southerly—the 19th century nickname for long-tailed ducks or oldsquaw. Unpublished in his lifetime, the essay combined all of young T.R.’s passions: open-water sailing, ornithology and hunting.

A 22-year-old Theodore Roosevelt first spotted the ducks as black specks on the horizon as his small sloop passed the mouth of the bay. Elliott, his younger brother, worked the tiller, fighting to keep the sails full as they pushed down on the birds. T.R. sat forward in the ready, shotgun in hand. The birds rafted tight together as the boat approached before “an old ‘pigeon tail’ took the alarm and rose,” T.R. would later write. He picked up his own gun, “and just as the great clump of birds ahead of us got fairly started at about thirty yards off we put all four barrels of no. 4 shot into them, and as we swept down through the flock put in four barrels more. The boat was left to herself and broached to; hauling in the sheets, one of us rushed to the bow with a long-handled scoop net, to pick up the birds. There were so many feathers floating on the water that it looked as if a pillow had burst over it.” The year 1880 was a busy one for Young Roosevelt. In March a doctor advised him against “the strenuous life” after diagnosing a heart condition on top of his chronic asthma. A few months later he graduated from Harvard magma cum laude, then took a trip to the Maine coast before a long upland hunt for grouse and prairie chicken in the upper Midwest. Back in the northeast that fall, he enrolled in Columbia Law School, married his first wife Alice Hathaway Lee in October, and was writing the final chapters in what would be his first book, The Naval War of 1812. Yet it was his duck hunt and sailing adventure on Long Island Sound he chose to memorialize that year in a short essay titled Sou’ Sou’ Southerly—the 19th century nickname for long-tailed ducks or oldsquaw. Unpublished in his lifetime, the essay combined all of young T.R.’s passions: open-water sailing, ornithology and hunting.