Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slaves in the United States from Interviews With Former Slaves Arkansas Narratives, Part 1 (Illustrated Edition)

Nonfiction, Social & Cultural Studies, Social Science, Discrimination & Race Relations, History, Americas, United States, Civil War Period (1850-1877)| Author: | Works Projects Administration | ISBN: | 9781475307030 |

| Publisher: | Charles River Editors | Publication: | April 27, 2012 |

| Imprint: | Language: | English |

| Author: | Works Projects Administration |

| ISBN: | 9781475307030 |

| Publisher: | Charles River Editors |

| Publication: | April 27, 2012 |

| Imprint: | |

| Language: | English |

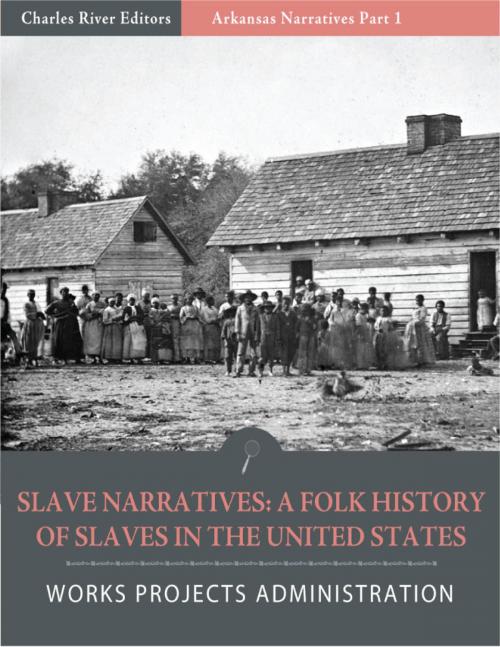

Slavery existed long before the United States of America was founded, but so did opposition to slavery. Both flourished after the founding of the country, and the anti-slavery movement was known as abolition. For many abolitionists, slavery was the preeminent moral issue of the day, and their opposition to slavery was rooted in deeply held religious beliefs. Quakers formed a significant part of the abolitionist movement in colonial times, as did certain Founding Fathers like Benjamin Franklin. Many other prominent opponents of slavery based their opposition in Enlightenment ideals and natural law. American abolitionists during the Constitutional Convention worked against the three-fifths compromise, and also attempted to get the Constitution to ban the Atlantic slave trade. Although the three-fifths compromise became a part of the Constitution, abolitionists managed to persuade the convention to allow Congress to ban the Atlantic slave trade after 1808. Other abolitionists tried to help slaves directly, by helping them escape to the North. After the Fugitive Slave Act mandated the return of escaped slaves, abolitionists helped escaped slaves travel to Canada. In addition, many northern politicians opposed restricting slavery as either practically impossible or dangerous. In the years after the Atlantic slave trade was banned in 1808, abolitionists focused their political efforts on preventing the spread of slavery to the new territory of the Louisiana Purchase. Pro-slavery politicians likewise attempted to spread slavery to new states. Every time a new state formed from Louisiana territory was to enter the Union, intense political wrangling took place over whether the new state would be slave or free. The political wrangling often broke into violence. By the middle of the 19th century, slavery had created a fevered pitch in the politics of the country, as abolitionists and slavery proponents fought a war of words and actual wars in Kansas and Nebraska. While the South postured for secession, abolitionists, both white and black, created a stronger movement in the Northeast in places like Boston. Ultimately the issue would have to be settled via civil war. There was a marked resurgence in interest in the institution of slavery in the 1920s and 30s. Private efforts sought to preserve the life histories of former slaves before they all died. With the advent of the New Deal, employment programs for jobless white-collar workers included the systematic collection of narratives from former slaves. These histories are a priceless collection collected by the Works Progress Administration, and are an invaluable source of data about the South, the institution of slavery, and the memories of those who had been enslaved. Over 2,300 stories were assembled into a 17 volume collection called Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slaves in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves. This is Part 1 of the Arkansas collection which includes 100 narratives. It is specially formatted with a Table of Contents and pictures of famous abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Harriet Beecher Stowe, as well as former slaves.

Slavery existed long before the United States of America was founded, but so did opposition to slavery. Both flourished after the founding of the country, and the anti-slavery movement was known as abolition. For many abolitionists, slavery was the preeminent moral issue of the day, and their opposition to slavery was rooted in deeply held religious beliefs. Quakers formed a significant part of the abolitionist movement in colonial times, as did certain Founding Fathers like Benjamin Franklin. Many other prominent opponents of slavery based their opposition in Enlightenment ideals and natural law. American abolitionists during the Constitutional Convention worked against the three-fifths compromise, and also attempted to get the Constitution to ban the Atlantic slave trade. Although the three-fifths compromise became a part of the Constitution, abolitionists managed to persuade the convention to allow Congress to ban the Atlantic slave trade after 1808. Other abolitionists tried to help slaves directly, by helping them escape to the North. After the Fugitive Slave Act mandated the return of escaped slaves, abolitionists helped escaped slaves travel to Canada. In addition, many northern politicians opposed restricting slavery as either practically impossible or dangerous. In the years after the Atlantic slave trade was banned in 1808, abolitionists focused their political efforts on preventing the spread of slavery to the new territory of the Louisiana Purchase. Pro-slavery politicians likewise attempted to spread slavery to new states. Every time a new state formed from Louisiana territory was to enter the Union, intense political wrangling took place over whether the new state would be slave or free. The political wrangling often broke into violence. By the middle of the 19th century, slavery had created a fevered pitch in the politics of the country, as abolitionists and slavery proponents fought a war of words and actual wars in Kansas and Nebraska. While the South postured for secession, abolitionists, both white and black, created a stronger movement in the Northeast in places like Boston. Ultimately the issue would have to be settled via civil war. There was a marked resurgence in interest in the institution of slavery in the 1920s and 30s. Private efforts sought to preserve the life histories of former slaves before they all died. With the advent of the New Deal, employment programs for jobless white-collar workers included the systematic collection of narratives from former slaves. These histories are a priceless collection collected by the Works Progress Administration, and are an invaluable source of data about the South, the institution of slavery, and the memories of those who had been enslaved. Over 2,300 stories were assembled into a 17 volume collection called Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slaves in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves. This is Part 1 of the Arkansas collection which includes 100 narratives. It is specially formatted with a Table of Contents and pictures of famous abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Harriet Beecher Stowe, as well as former slaves.