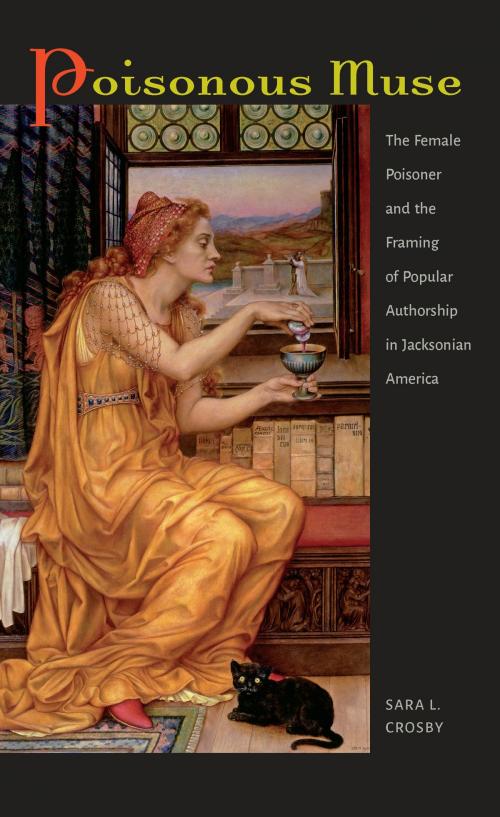

Poisonous Muse

The Female Poisoner and the Framing of Popular Authorship in Jacksonian America

Fiction & Literature, Literary Theory & Criticism| Author: | Sara L. Crosby | ISBN: | 9781609384043 |

| Publisher: | University of Iowa Press | Publication: | April 15, 2016 |

| Imprint: | University Of Iowa Press | Language: | English |

| Author: | Sara L. Crosby |

| ISBN: | 9781609384043 |

| Publisher: | University of Iowa Press |

| Publication: | April 15, 2016 |

| Imprint: | University Of Iowa Press |

| Language: | English |

The nineteenth century was, we have been told, the “century of the poisoner,” when Britain and the United States trembled under an onslaught of unruly women who poisoned husbands with gleeful abandon. That story, however, is only half true. While British authorities did indeed round up and execute a number of impoverished women with minimal evidence and fomented media hysteria, American juries refused to convict suspected women and newspapers laughed at men who feared them.

This difference in outcome doesn’t mean that poisonous women didn’t preoccupy Americans. In the decades following Andrew Jackson’s first presidential bid, Americans buzzed over women who used poison to kill men. They produced and devoured reams of ephemeral newsprint, cheap trial transcripts, and sensational “true” pamphlets, as well as novels, plays, and poems. Female poisoners served as crucial elements in the literary manifestos of writers from Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe to George Lippard and the cheap pamphleteer E. E. Barclay, but these characters were given a strangely positive spin, appearing as innocent victims, avenging heroes, or engaging humbugs.

The reason for this poison predilection lies in the political logic of metaphor. Nineteenth-century Britain strove to rein in democratic and populist movements by labeling popular print “poison” and its providers “poisoners,” drawing on centuries of established metaphor that negatively associated poison, women, and popular speech or writing. Jacksonian America, by contrast, was ideologically committed to the popular—although what and who counted as such was up for serious debate. The literary gadfly John Neal called on his fellow Jacksonian writers to defy British critical standards, saying, “Let us have poison.” Poisonous Muse investigates how they answered, how they deployed the figure of the female poisoner to theorize popular authorship, to validate or undermine it, and to fight over its limits, particularly its political, gendered, and racial boundaries.

Poisonous Muse tracks the progress of this debate from approximately 1820 to 1845. Uncovering forgotten writers and restoring forgotten context to well-remembered authors, it seeks to understand Jacksonian print culture from the inside out, through its own poisonous language.

The nineteenth century was, we have been told, the “century of the poisoner,” when Britain and the United States trembled under an onslaught of unruly women who poisoned husbands with gleeful abandon. That story, however, is only half true. While British authorities did indeed round up and execute a number of impoverished women with minimal evidence and fomented media hysteria, American juries refused to convict suspected women and newspapers laughed at men who feared them.

This difference in outcome doesn’t mean that poisonous women didn’t preoccupy Americans. In the decades following Andrew Jackson’s first presidential bid, Americans buzzed over women who used poison to kill men. They produced and devoured reams of ephemeral newsprint, cheap trial transcripts, and sensational “true” pamphlets, as well as novels, plays, and poems. Female poisoners served as crucial elements in the literary manifestos of writers from Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe to George Lippard and the cheap pamphleteer E. E. Barclay, but these characters were given a strangely positive spin, appearing as innocent victims, avenging heroes, or engaging humbugs.

The reason for this poison predilection lies in the political logic of metaphor. Nineteenth-century Britain strove to rein in democratic and populist movements by labeling popular print “poison” and its providers “poisoners,” drawing on centuries of established metaphor that negatively associated poison, women, and popular speech or writing. Jacksonian America, by contrast, was ideologically committed to the popular—although what and who counted as such was up for serious debate. The literary gadfly John Neal called on his fellow Jacksonian writers to defy British critical standards, saying, “Let us have poison.” Poisonous Muse investigates how they answered, how they deployed the figure of the female poisoner to theorize popular authorship, to validate or undermine it, and to fight over its limits, particularly its political, gendered, and racial boundaries.

Poisonous Muse tracks the progress of this debate from approximately 1820 to 1845. Uncovering forgotten writers and restoring forgotten context to well-remembered authors, it seeks to understand Jacksonian print culture from the inside out, through its own poisonous language.