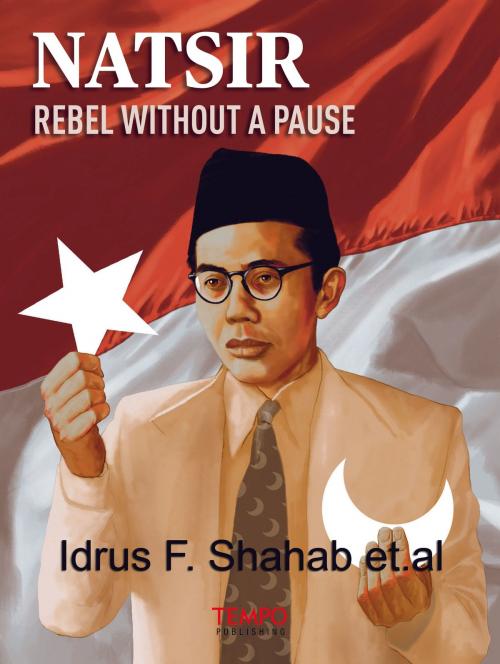

| Author: | Idrus F. Shahab et al. | ISBN: | 9781301334056 |

| Publisher: | Tempo Publishing | Publication: | August 19, 2013 |

| Imprint: | Smashwords Edition | Language: | English |

| Author: | Idrus F. Shahab et al. |

| ISBN: | 9781301334056 |

| Publisher: | Tempo Publishing |

| Publication: | August 19, 2013 |

| Imprint: | Smashwords Edition |

| Language: | English |

MOHAMMAD Natsir (July 17, 1908-February 6, 1993) was a puritan. However, even the honest can be interesting. His life was not as colorful or dramatic as a stage play, but the example set by this person, who had a talent for combining words with deeds, was nothing less than remarkable. With Indonesia currently going through a kind of vicious circle—new leaders taking over, yet an efficient bureaucracy, clean politics and an effective social welfare system still beyond the people’s reach— Natsir emerges as a leader who escaped that cycle. He was clean, consistent and although sharp toned when defending his position, he was a humble man.

In the book, The Life and Struggles of Natsir: 70 Years of Memories, George McTurnan Kahin, an American scholar on Indonesia who sympathized with the Indonesian struggle for independence at that time, recalled the impression Natsir made on their first meeting. As Minister of Information, he spoke openly about what was going on in Indonesia. However, what really stuck in Kahin’s mind was the Minister’s appearance. “He was wearing a patched-up shirt, something I have never seen among government officials anywhere,” said Kahin.

Perhaps that is why to this day—during the centennial of his birth and 15 years after his death—many believe that Mohammad Natsir is part of our contemporary life. Many like to identify themselves with Natsir. Islamic hardliners, for instance, tend to forget how close his ideas were with Western democracy, while pointing out his distress at the zeal of Christian missionaries in Indonesia. Moderate Muslims seem to have the same selective political memory. Many have forgotten the period when this former Prime Minister, who represented the Masyumi Party, led the Islamic Propagation Council (Dewan Dakwah). Meanwhile, others may recall the period when differences of opinion could not divide the country. Pluralism, at that time, was commonplace.

Mohammad Natsir lived at a time when friendship across ideological lines was not ground for suspicion, nor was it a betrayal. He was fundamentally against communism. In fact, his later involvement in the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PRRI) was caused by, among other factors, his disapproval of the Sukarno administration, which he felt was getting closer to the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). Masyumi and the PKI were two groups which could never meet. Natsir knew, however, that political identity was not absolute. He often shared a cup of coffee with D.N. Aidit at the parliament’s canteen, even though Aidit was then head of the PKI’s Central Committee.

MOHAMMAD Natsir (July 17, 1908-February 6, 1993) was a puritan. However, even the honest can be interesting. His life was not as colorful or dramatic as a stage play, but the example set by this person, who had a talent for combining words with deeds, was nothing less than remarkable. With Indonesia currently going through a kind of vicious circle—new leaders taking over, yet an efficient bureaucracy, clean politics and an effective social welfare system still beyond the people’s reach— Natsir emerges as a leader who escaped that cycle. He was clean, consistent and although sharp toned when defending his position, he was a humble man.

In the book, The Life and Struggles of Natsir: 70 Years of Memories, George McTurnan Kahin, an American scholar on Indonesia who sympathized with the Indonesian struggle for independence at that time, recalled the impression Natsir made on their first meeting. As Minister of Information, he spoke openly about what was going on in Indonesia. However, what really stuck in Kahin’s mind was the Minister’s appearance. “He was wearing a patched-up shirt, something I have never seen among government officials anywhere,” said Kahin.

Perhaps that is why to this day—during the centennial of his birth and 15 years after his death—many believe that Mohammad Natsir is part of our contemporary life. Many like to identify themselves with Natsir. Islamic hardliners, for instance, tend to forget how close his ideas were with Western democracy, while pointing out his distress at the zeal of Christian missionaries in Indonesia. Moderate Muslims seem to have the same selective political memory. Many have forgotten the period when this former Prime Minister, who represented the Masyumi Party, led the Islamic Propagation Council (Dewan Dakwah). Meanwhile, others may recall the period when differences of opinion could not divide the country. Pluralism, at that time, was commonplace.

Mohammad Natsir lived at a time when friendship across ideological lines was not ground for suspicion, nor was it a betrayal. He was fundamentally against communism. In fact, his later involvement in the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia (PRRI) was caused by, among other factors, his disapproval of the Sukarno administration, which he felt was getting closer to the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). Masyumi and the PKI were two groups which could never meet. Natsir knew, however, that political identity was not absolute. He often shared a cup of coffee with D.N. Aidit at the parliament’s canteen, even though Aidit was then head of the PKI’s Central Committee.