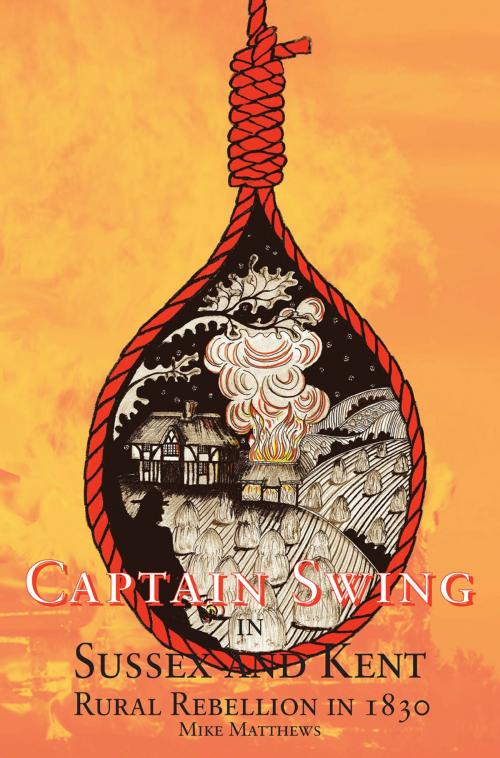

Captain Swing in Sussex and Kent: Rural Rebellion in 1830

The Untold Story of Rural Class War in the South-East

Nonfiction, History, Revolutionary, Modern, 19th Century, British| Author: | Mike Matthews | ISBN: | 1230000270778 |

| Publisher: | ChristieBooks | Publication: | September 28, 2014 |

| Imprint: | ChristieBooks | Language: | English |

| Author: | Mike Matthews |

| ISBN: | 1230000270778 |

| Publisher: | ChristieBooks |

| Publication: | September 28, 2014 |

| Imprint: | ChristieBooks |

| Language: | English |

IN 1830, after the prolonged agricultural recession that followed the close of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, a series of riots swept across England’s southern counties. The outbreaks went on to spread, largely unchecked, into East Anglia, the Midlands and several northern counties, eventually to reach Carlisle. The economic hardship of the long-suffering, wretchedly oppressed and half-starved labourers had become so acute that their usual forbearance finally snapped. This agrarian rebellion was fuelled by an unprecedented level of class hatred and bitterness. Driven by a blind desire for revenge and reprisal against the farmers and their wealthy friends, the farmhands were set on a course of violent, direct retaliatory action, regardless of the consequences.

Mike Matthews, the author charts Swing’s progress through just two southern counties, Kent and Sussex, which suffered the greatest levels of incendiarism and destruction of machinery, but this is not a comprehensive regional study of the riots, since to list in chronological order one lawless episode after another would soon become very tedious for the reader: the destruction of farm premises and machinery in Kent and Sussex was on an immense scale, as will become abundantly clear in this narrative. Wherever possible he has tried to avoid duplicating existing published material on Swing, and, whenever feasible, has attempted to combine all the previous historical information on the riots into detailed case-studies of various size. Two chapters contain subject matter relating to the outbreaks that has never before been seen in print and readers interested in the emergence of agricultural trade unionism will learn something new.

Captain Swing explores, closely, what county and national reporters in 1830 were calling a ‘war of poverty against property’, a civil strife of ‘destitution against possession’, and breathes new life and colour into the criminal exploits and violent resistance of the Captain Swing insurgents, to endeavour to understand what their contemporaries described apprehensively as ‘their dark mischief’ and ‘state of reckless insubordination’.

IN 1830, after the prolonged agricultural recession that followed the close of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, a series of riots swept across England’s southern counties. The outbreaks went on to spread, largely unchecked, into East Anglia, the Midlands and several northern counties, eventually to reach Carlisle. The economic hardship of the long-suffering, wretchedly oppressed and half-starved labourers had become so acute that their usual forbearance finally snapped. This agrarian rebellion was fuelled by an unprecedented level of class hatred and bitterness. Driven by a blind desire for revenge and reprisal against the farmers and their wealthy friends, the farmhands were set on a course of violent, direct retaliatory action, regardless of the consequences.

Mike Matthews, the author charts Swing’s progress through just two southern counties, Kent and Sussex, which suffered the greatest levels of incendiarism and destruction of machinery, but this is not a comprehensive regional study of the riots, since to list in chronological order one lawless episode after another would soon become very tedious for the reader: the destruction of farm premises and machinery in Kent and Sussex was on an immense scale, as will become abundantly clear in this narrative. Wherever possible he has tried to avoid duplicating existing published material on Swing, and, whenever feasible, has attempted to combine all the previous historical information on the riots into detailed case-studies of various size. Two chapters contain subject matter relating to the outbreaks that has never before been seen in print and readers interested in the emergence of agricultural trade unionism will learn something new.

Captain Swing explores, closely, what county and national reporters in 1830 were calling a ‘war of poverty against property’, a civil strife of ‘destitution against possession’, and breathes new life and colour into the criminal exploits and violent resistance of the Captain Swing insurgents, to endeavour to understand what their contemporaries described apprehensively as ‘their dark mischief’ and ‘state of reckless insubordination’.