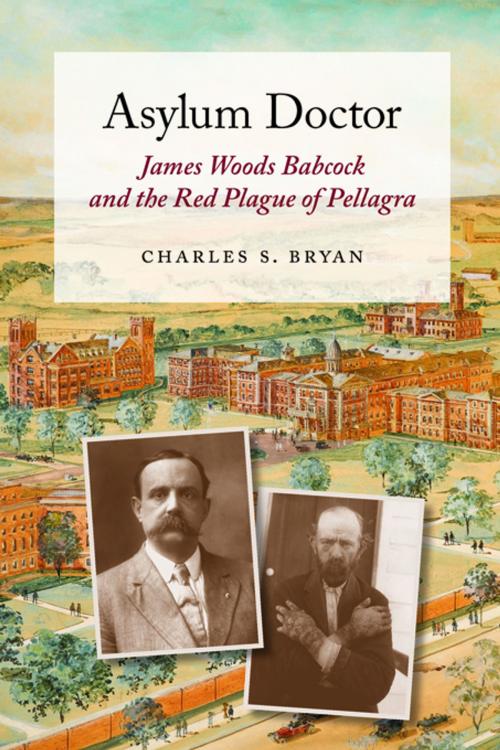

Asylum Doctor

James Woods Babcock and the Red Plague of Pellagra

Nonfiction, Health & Well Being, Medical, Reference, History, Biography & Memoir, Social & Cultural Studies, Social Science| Author: | Charles S. Bryan | ISBN: | 9781611174915 |

| Publisher: | University of South Carolina Press | Publication: | May 27, 2014 |

| Imprint: | University of South Carolina Press | Language: | English |

| Author: | Charles S. Bryan |

| ISBN: | 9781611174915 |

| Publisher: | University of South Carolina Press |

| Publication: | May 27, 2014 |

| Imprint: | University of South Carolina Press |

| Language: | English |

During the early twentieth century thousands of Americans died of pellagra before the cause—vitamin B3 deficiency—was identified. Credit for ending the scourge is usually given to Dr. Joseph Goldberger of the U.S. Public Health Service, who proved the case for dietary deficiency during 1914−1915 and spent the rest of his life combating those who refused to accept southern poverty as the root cause. Charles S. Bryan demonstrates that between 1907 and 1914 a patchwork coalition of American asylum superintendents, local health officials, and practicing physicians developed a competence in pellagra, sifted through hypotheses, and set the stage for Goldberger’s epic campaign. Leading the American response to pellagra was Dr. James Woods Babcock (1856–1922), superintendent of the South Carolina State Hospital for the Insane from 1891 to 1914. It was largely Babcock who sounded the alarm, brought out the first English-language treatise on pellagra, and organized the National Association for the Study of Pellagra, the three meetings of which—all at the woefully underfunded Columbia asylum—were landmarks in the history of the disease. More than anyone else, Babcock encouraged pellagra researchers on both sides of the Atlantic. Bryan proposes that the early response to pellagra constitutes an underappreciated chapter in the coming-of-age of American medical science. The book also includes a history of mental health administration in South Carolina during the early twentieth century and reveals the complicated, troubled governance of the asylum. Bryan concludes that the traditional bane of good administration in South Carolina and excessive General Assembly oversight, coupled with Governor Cole Blease’s political intimidation and unblushing racism, damaged the asylum and drove Babcock from his post as superintendent. Remarkably many of the issues of inadequate funding, political cronyism, and meddling in the state’s health care facilities reemerged in modern times. Asylum Doctor describes the plight of the mentally ill during an era when public asylums had devolved into convenient places to warehouse inconvenient people. It is the story of an idealistic humanitarian who faced conditions most people would find intolerable. And it is important social history for, as this book’s epigraph puts it, “in many ways the Old South died with the passing of pellagra.”

During the early twentieth century thousands of Americans died of pellagra before the cause—vitamin B3 deficiency—was identified. Credit for ending the scourge is usually given to Dr. Joseph Goldberger of the U.S. Public Health Service, who proved the case for dietary deficiency during 1914−1915 and spent the rest of his life combating those who refused to accept southern poverty as the root cause. Charles S. Bryan demonstrates that between 1907 and 1914 a patchwork coalition of American asylum superintendents, local health officials, and practicing physicians developed a competence in pellagra, sifted through hypotheses, and set the stage for Goldberger’s epic campaign. Leading the American response to pellagra was Dr. James Woods Babcock (1856–1922), superintendent of the South Carolina State Hospital for the Insane from 1891 to 1914. It was largely Babcock who sounded the alarm, brought out the first English-language treatise on pellagra, and organized the National Association for the Study of Pellagra, the three meetings of which—all at the woefully underfunded Columbia asylum—were landmarks in the history of the disease. More than anyone else, Babcock encouraged pellagra researchers on both sides of the Atlantic. Bryan proposes that the early response to pellagra constitutes an underappreciated chapter in the coming-of-age of American medical science. The book also includes a history of mental health administration in South Carolina during the early twentieth century and reveals the complicated, troubled governance of the asylum. Bryan concludes that the traditional bane of good administration in South Carolina and excessive General Assembly oversight, coupled with Governor Cole Blease’s political intimidation and unblushing racism, damaged the asylum and drove Babcock from his post as superintendent. Remarkably many of the issues of inadequate funding, political cronyism, and meddling in the state’s health care facilities reemerged in modern times. Asylum Doctor describes the plight of the mentally ill during an era when public asylums had devolved into convenient places to warehouse inconvenient people. It is the story of an idealistic humanitarian who faced conditions most people would find intolerable. And it is important social history for, as this book’s epigraph puts it, “in many ways the Old South died with the passing of pellagra.”