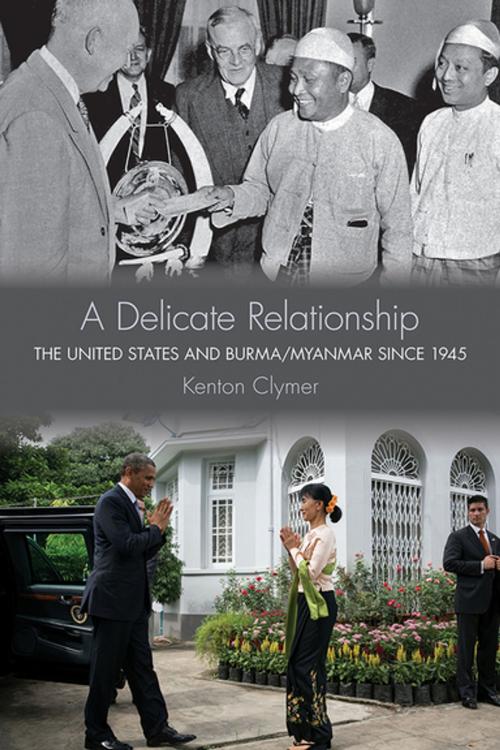

A Delicate Relationship

The United States and Burma/Myanmar since 1945

Nonfiction, History, Asian, Southeast Asia, Americas, United States, 20th Century| Author: | Kenton Clymer | ISBN: | 9781501701016 |

| Publisher: | Cornell University Press | Publication: | February 19, 2016 |

| Imprint: | Cornell University Press | Language: | English |

| Author: | Kenton Clymer |

| ISBN: | 9781501701016 |

| Publisher: | Cornell University Press |

| Publication: | February 19, 2016 |

| Imprint: | Cornell University Press |

| Language: | English |

In 2012, Barack Obama became the first U.S. president ever to visit Myanmar, formerly known as Burma. This official state visit marked a new period in the long and sinuous diplomatic relationship between the United States and Burma/Myanmar, which Kenton Clymer examines in A Delicate Relationship. From the challenges of decolonization and heightened nationalist activities that emerged in the wake of World War II to the Cold War concern with domino states to the rise of human rights policy in the 1980s and beyond, Clymer demonstrates how Burma/Myanmar has fit into the broad patterns of U.S. foreign policy and yet has never been fully integrated into diplomatic efforts in the region of Southeast Asia.

When Burma, a British colony since the nineteenth century, achieved independence in 1948, the United States feared that the country might be the first Southeast Asian nation to fall to the communists, and it embarked on a series of efforts to prevent this. In 1962, General Ne Win, who toppled the government in a coup d’état, established an authoritarian socialist military junta that severely limited diplomatic contact and led to a period in which the primary American diplomatic concern became Burma’s increasing opium production. Ne Win’s rule ended (at least officially) in 1988, when the Burmese people revolted against the oppressive military government. Aung San Suu Kyi emerged as the charismatic leader of the opposition and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. Amid these great changes in policy and outlook, Burma/Myanmar remained fiercely nonaligned and, under Ne Win, isolationist. The limited diplomatic exchange that resulted meant that the state was often a frustrating puzzle to U.S. officials.

Clymer explores attitudes toward Burma (later Myanmar), from anxious anticommunism during the Cold War to interventions to stop drug trafficking to debates in Congress, the White House, and the Department of State over how to respond to the emergence of the opposition movement in the late 1980s. The junta’s brutality, its refusal to relinquish power, and its imprisonment of opposition leaders resulted in public and Congressional pressure to try to change the regime. Indeed, Aung San Suu Kyi’s rise to prominence fueled the new foreign policy debate that was focused on human rights, and in that climate Burma/Myanmar held particularly large symbolic importance for U.S. policy makers. Congressional and public opinion favored sanctions, while U.S. presidents and their administrations were more cautious. Clymer’s account concludes with President Obama’s visits in 2012 and 2014, and visits to the United States by Aung San Suu Kyi and President Thein Sein, which marked the establishment of a new, warmer relationship with a relatively open Myanmar.

In 2012, Barack Obama became the first U.S. president ever to visit Myanmar, formerly known as Burma. This official state visit marked a new period in the long and sinuous diplomatic relationship between the United States and Burma/Myanmar, which Kenton Clymer examines in A Delicate Relationship. From the challenges of decolonization and heightened nationalist activities that emerged in the wake of World War II to the Cold War concern with domino states to the rise of human rights policy in the 1980s and beyond, Clymer demonstrates how Burma/Myanmar has fit into the broad patterns of U.S. foreign policy and yet has never been fully integrated into diplomatic efforts in the region of Southeast Asia.

When Burma, a British colony since the nineteenth century, achieved independence in 1948, the United States feared that the country might be the first Southeast Asian nation to fall to the communists, and it embarked on a series of efforts to prevent this. In 1962, General Ne Win, who toppled the government in a coup d’état, established an authoritarian socialist military junta that severely limited diplomatic contact and led to a period in which the primary American diplomatic concern became Burma’s increasing opium production. Ne Win’s rule ended (at least officially) in 1988, when the Burmese people revolted against the oppressive military government. Aung San Suu Kyi emerged as the charismatic leader of the opposition and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. Amid these great changes in policy and outlook, Burma/Myanmar remained fiercely nonaligned and, under Ne Win, isolationist. The limited diplomatic exchange that resulted meant that the state was often a frustrating puzzle to U.S. officials.

Clymer explores attitudes toward Burma (later Myanmar), from anxious anticommunism during the Cold War to interventions to stop drug trafficking to debates in Congress, the White House, and the Department of State over how to respond to the emergence of the opposition movement in the late 1980s. The junta’s brutality, its refusal to relinquish power, and its imprisonment of opposition leaders resulted in public and Congressional pressure to try to change the regime. Indeed, Aung San Suu Kyi’s rise to prominence fueled the new foreign policy debate that was focused on human rights, and in that climate Burma/Myanmar held particularly large symbolic importance for U.S. policy makers. Congressional and public opinion favored sanctions, while U.S. presidents and their administrations were more cautious. Clymer’s account concludes with President Obama’s visits in 2012 and 2014, and visits to the United States by Aung San Suu Kyi and President Thein Sein, which marked the establishment of a new, warmer relationship with a relatively open Myanmar.